JULY 4, 2019 – As go Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Presidents Day, so goes the Fourth of July. In other words, the fashion in which we celebrate these holidays is quite detached from the historical reality of their origins.

In the case of Independence Day, where is the meaning in fireworks, local parades, fireworks, backyard barbecues, fireworks, and red, white, and blue? How do they qualify as the dominant forms of satisfying a national commemoration imperative?

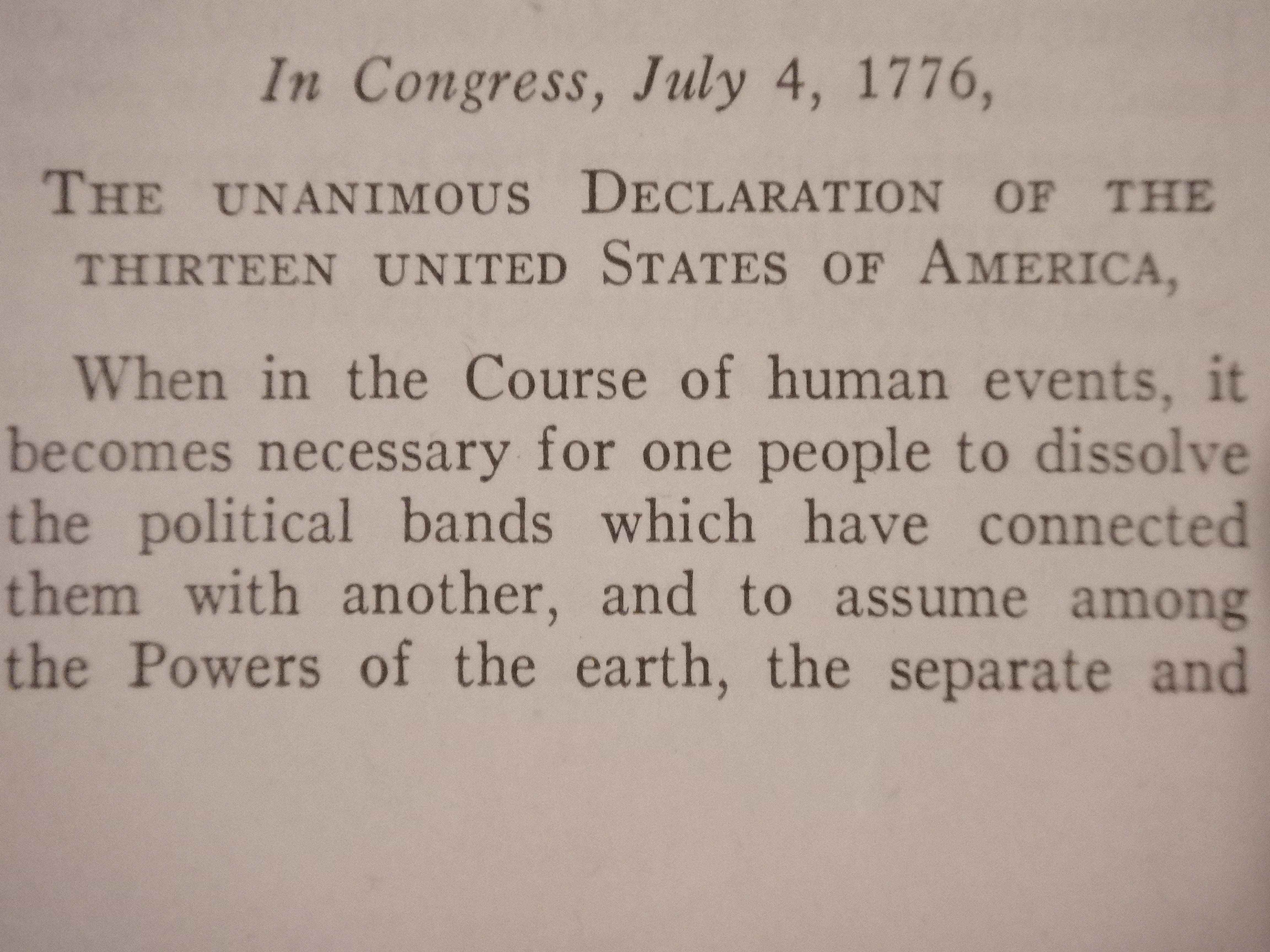

When I was an early school kid, I was under the mistaken impression that July 4, 1776 marked the beginning, the middle, and the end of the American Revolution. I mean, what else would justify all the festivities—all the noise—on the Fourth of July if our separation from Great Britain wasn’t on that day, a done deal?

By fifth grade I learned that the Declaration of Independence was only that—a declaration. I realized that words were cheap, or at least, simple, however elegantly arranged. The hard, messy, bloody part followed for more than five years.

However definitive the British surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, e pluribus unum was still far from being a done deal. The Treaty of Paris, which actually ended the conflict, wasn’t signed until late 1783, and wasn’t ratified by the American Congress of the Confederation until early 1784. Our nation wasn’t fully constituted until May 29, 1790, the date on which the last of the original 13 colonies, Rhode Island, ratified the Constitution.

Ratification had not been easy. Anti-federalists had lined up with a vengeance against the Constitution. Their campaign was countered by John Jay, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, who together wrote and disseminated The Federalist (later known as The Federalist Papers) supporting the case for ratification. In the end the federalists prevailed but by a whisker: Rhode Island’s ratification convention approved by just two votes.

But much of all that complicated history is lost somewhere between the potato chips and the potato salad. Over time we’ve evolved into a society within a world that none of The Founders could begin to fathom without a strong shot of (Irish?) whiskey.

Today’s celebration is guided little by historical insight but a lot by our national obsession with team sports. In fact, the Fourth has become a team sport. It’s all about cheering the home team, shooting off fireworks (albeit made in China against whom we are ramping up a trade war), and sporting the team colors of red, white, and blue.

In this last bit—the colors—lies great irony. How many Americans, I wonder, who wrap themselves in red, white, and blue on this day are mindful that those are the same colors of the nation from which we Americans strove to be independent? And how many Americans understand that our Revolution was at base a conservative one, led by landed gentry and wealthy merchants, not by masses of the truly oppressed–black slaves, for instance?

So, go forth–I mean, “Go Fourth!” But remember, it was early in the game. And the end of slavery would be another whole bloody ball game.

© 2019 Eric Nilsson