DECEMBER 19, 2020 – Recently, while combing through boxes of old papers, I discovered my “day file” from a year of my early law practice. The file contained copies of letters bound at the top and arranged in chronological order. Back in the day, my secretary would make two copies of every letter or memo that went out of my office, put one copy in the appropriate client file and place the other copy in my “day file.” The latter repository served as a “back-up” system.

Thumbing through the three-inch stack of letters was like watching a fast-motion, vintage movie. It worked as a low-budget documentary of “old times.” Perhaps the only person who’d ever be interested in its contents is an anthropology PhD candidate 10,000 years from now, assuming that (a) miraculously, my “day file” survives (encased in volcanic ash?); AND (b) little else of our epoch survives–except “PhDs“ and “anthropology.”

Back in the day of the “day file,” a letter took time. First was the dictation. “This letter is to [So-and-So],” you’d start; then say, “I want it to go by [fax, regular mail or messenger].” Next you’d dictate—starting and stopping the “REC” function on your hand-held recording device equipped with miniature cassette tapes. You’d then put the tape in the designated box on your secretary’s desk and await the outcome.

Once the draft returned, you’d mark it up, hand it back to the secretary, and return calls among your (paper) phone messages while the final (you hoped) version of the letter was in production.

Eventually the letter would go out the door, and copies would wind up in the client’s file and . . . the “day file.”

Today, of course, to kick out a letter you turn your keyboard into a machine gun. You pull the trigger and a copy of the damage winds up in the cloud. Long gone are the “secretary” and . . . the “day file.”

Now think “photographs.” Back in the day, after accumulating three rolls of 36 images, you dropped the rolls off at your local drug store. A few days later, you retrieved the developed photos, maybe stuck a few in an album, shoved the rest back in the envelopes and consigned them to the attic.

Which makes me wonder: what record of our times will survive—our times?

Sure, the “day file” could go up in flames or, more likely, wind up finely shredded (or not) before being recycled into toilet paper or simply dumped in the trash and hauled straight away to a landfill. But what about the trillions of email, photos, and social media posts we generate? They’re all sitting on server farms somewhere in Utah, Iowa—or Sweden—in the form of ones and zeros squeezed onto slivers of silica housed inside flimsy metal cases resting on shelves inside sprawling, climate-controlled complexes . It might all look secure and accessible today, but 100 years from now? A thousand? Don’t count on it.

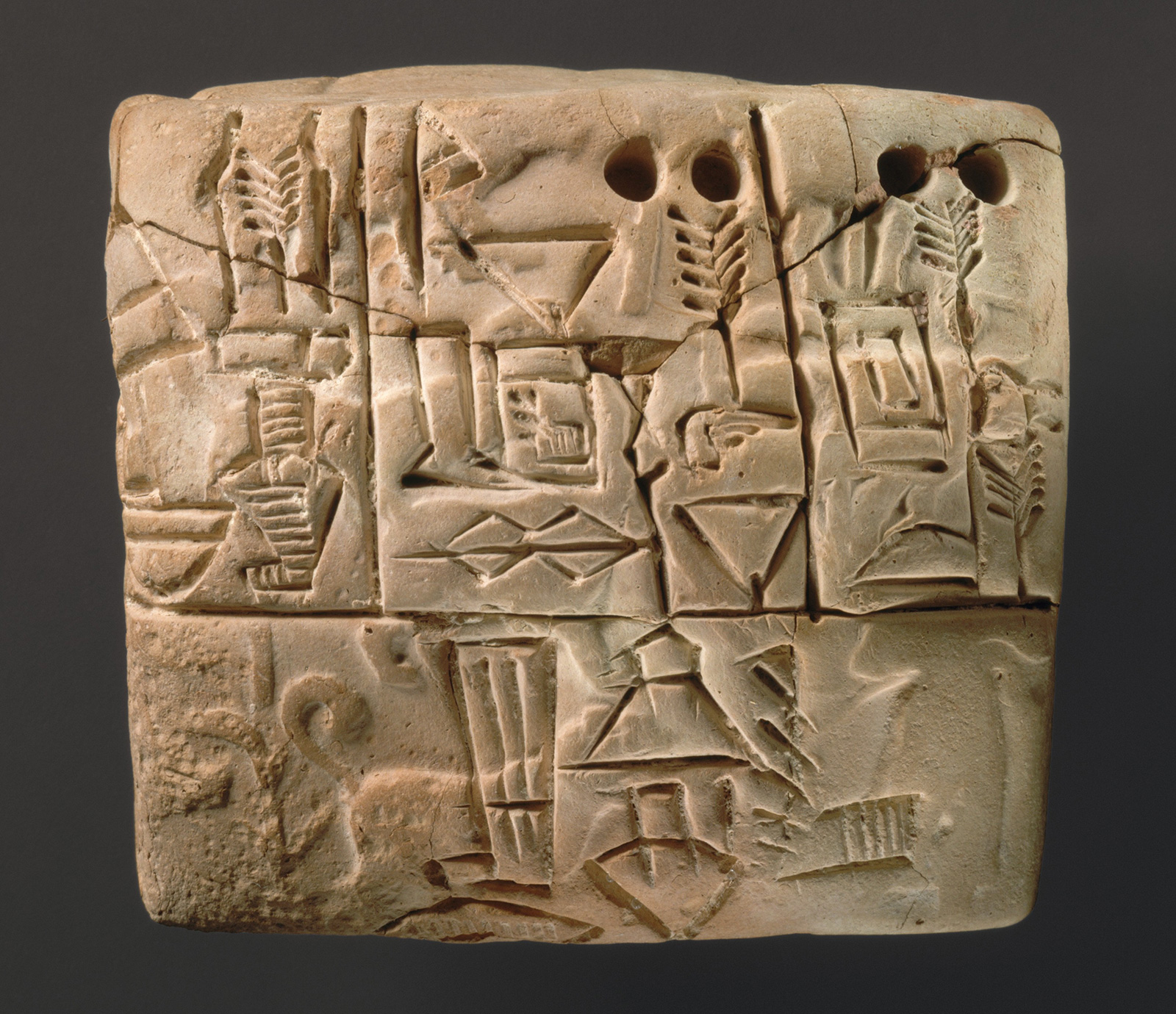

As it turns out, with their cave paintings and cuneiform, our ancient ancestors might have been way ahead of our times.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2020 by Eric Nilsson