FEBRUARY 17, 2023 – Last night I experienced an unusual dream segment. It was connected to a long, diverse chain of dreams; a seemingly endless train like the one that ambles past a crossing on my way to downtown St. Paul whenever I’m running late.

With several acquaintances, I was standing in a hallway somewhere. Without any other context, someone at a grand piano in an adjoining room started playing the Adagio from Beethoven’s Pathètique. I’ve heard the piece a million times—at least—but I can’t remember my most recent exposure to it. What surprised me, both in the course of the dream and upon waking, is that I heard the five-and-a-half minute piece played in its entirety.

Over this morning’s coffee installment, I wondered how and why my sleeping brain had assembled the Pathètique Adagio in whole cloth. I’m not a pianist and I’d never committed the whole piece to memory, although throughout my early childhood, Dad played it on a regular basis.

Ah ha! There was my clue—along with a second: a recent walk with my good friend Sally, law school classmate and long-time piano collaborator, who performed the piece on one of our house concerts seven or eight years ago. In fact, that was probably the most recent time I’d heard the Pathètique performed live.

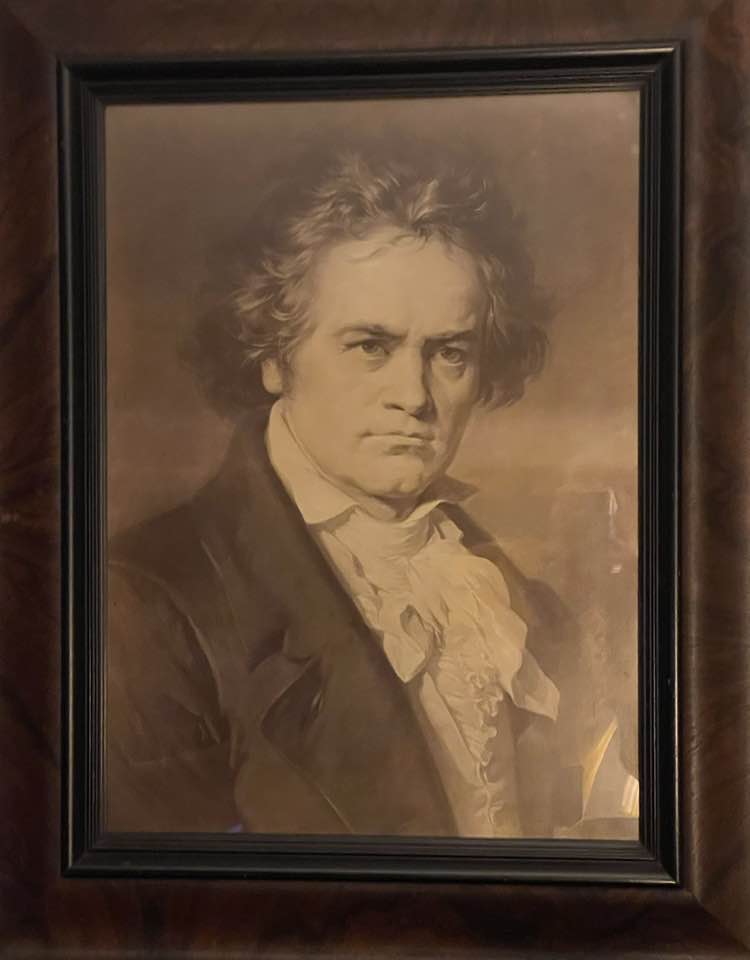

No one besides my sister Elsa loves the music of Beethoven as much as Dad did. Not even Mother, whose students were greeted by the Titan’s portrait when they entered her piano studio. Whereas Mother was game to sightread anything you placed before her—Beethoven or otherwise—Dad would play only pieces that he’d perfected. Moreover, his musical interpretation was always as moving as his technical mastery of a piece. The Pathètique was one such work.

One of my most vivid, early memories features Dad at the piano in the evening, placing the Beethoven on the rack, opening it to the Pathètique and . . . filling my ears with it. His gaze was riveted to the music in such a way I thought everything in the room would shatter if his playing were interrupted. I worried that Mother or one of my sisters would call out to him from two rooms away.

The other thing I remember is how he moved his hands and fingers with complete economy over the keyboard. He exercised magnificent control and efficiency over every muscle, every movement to draw exactly what he wanted from the music. And that music was magically beautiful to my young ears. He never tired of playing the Beethoven, and I never wearied of hearing it.

I also remember distinctly that when I heard Sally play the Pathètique, I thought of Dad’s association with it. So circling back to the dream segment, it all makes sense. Our earliest memories are the deepest ones. Of the millions of subconscious thoughts and memories bouncing around inside our heads, a small group coalesces into a dream. Each coalescence is triggered by a catalyst of some sort—a related subconscious thought or memory.

Dreams are a wild kaleidoscope of possibilities deep inside our brains. Consider for example what thoughts and memories coalesced and by some catalyst produced the dream in which I met Enver Hoxha, dictator of Albania from 1944 to 1985, in an old general store in Tirana.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson