MARCH 27, 2025 – Here’s the question that dogs me whenever I consider a major issue of public concern: Can I—never “Do I”—ever know what I’m talking about? Another way of presenting the question is, Can I ever grasp, synthesize, analyze and draw a reasonable conclusion from . . . drum roll, drum roll . . . all the material irrefutable facts?

Of course, this is in large manner a trick question. About very few things in the public realm can one identify all the qualifying facts (material and indisputable). If the requisite level of diligence were to be achieved, one would have to dispense with all other concerns in life. Only a savant has the capacity to know everything that is necessary to form a fully informed judgment about any complex issue, from energy to health care to education to foreign policy to the economy. It would be unfair, not to mention unrealistic, to expect ourselves to be savants about much of anything, though I have encountered a number of people who I’m sure qualify as savants. Their “savantism,” however, is quirky (often associated with autism) and though impressive as far as it goes, none of these savants has offered much of a solution to any of society’s imponderable problems.

Typical is a friend of one of my nieces. I’ve not met the gentleman, but my sister has. This unusual man has committed to memory the daily flight schedules of several major airlines. Want to catch an early afternoon flight from Cleveland to Philly? United number 2345 departing at 1:30 is the one for you. But what to do about Ukraine? Our plane schedule savant wouldn’t have a clue. My neighbor the literary savant, on the other hand, is not afraid to talk politics, and I can assure you that he has a strident opinion about Ukraine, which view is not to be casually dismissed: my friend is exceptionally well informed. But he knows far more about American and British literature than he does about the history of Galicia, the Donbas, and Crimea—i.e. the backdrop of what we call Ukraine.

I’m certainly no savant in any compartment of highly specialized knowledge or intelligence. But my point here is that it wouldn’t matter if I were some kind of special recognized authority in a given field of endeavor. Across the board, I’m very much a generalist, or to dress it up a bit, a “liberal arts major.” This is fine as far as it goes. This level of non-expertise permits me to maintain a level of curiosity sufficient to avoid boredom. It does not, however, allow me to weigh in knowledgeably—I mean really, truly knowledgeably—about much of anything of broad public interest.

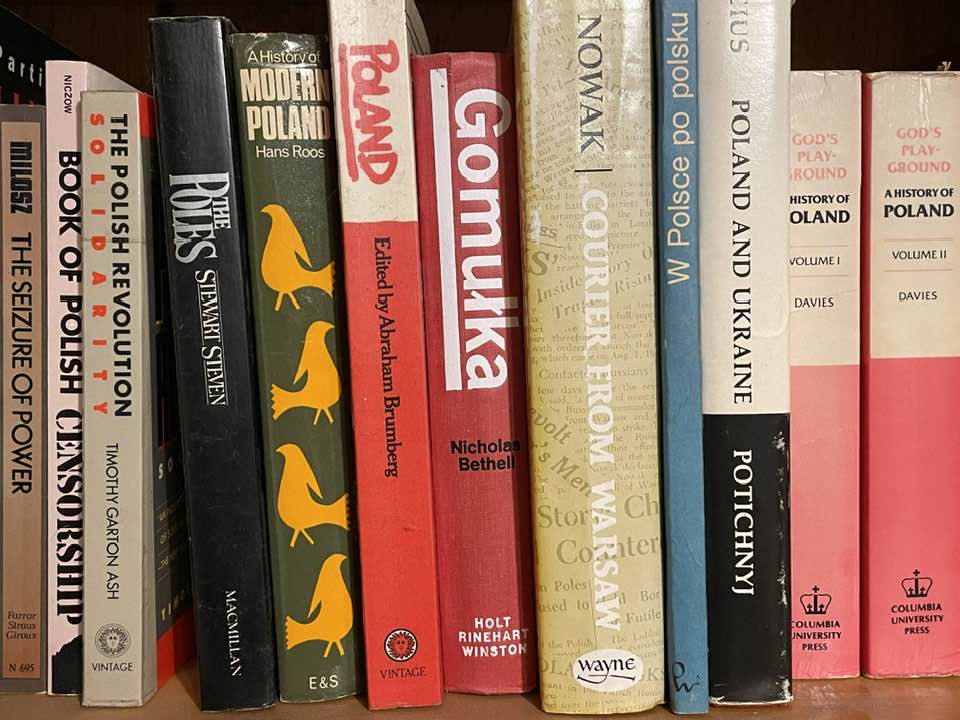

I’ve been reminded of this inescapable reality by my daily diet of reading for my undergraduate university class in Russian history. The farther I wade, the faster the tide seems to ebb. I feel as though I’ll be in perpetually shallow waters, no matter how far and long I proceed. For every book I read and study, 10 more are added to my list. And of course, with a country as vast as Russia in both its geographical sense and historical breadth, a study of that country necessarily requires deep inquiry into the examination of the many other lands, people, cultures whose fates and fortunes have been intertwined with Russia and one another.

What we call Ukraine has played a major role in the story of Russia, and continues, of course, to be at center stage. Ukraine has become the poster child of my paradoxical experience with the study of history: the more I scratch the surface, the more surface I scratch—not “the deeper I plunge.” Do I still oppose what Putin has done to Ukraine? Absolutely. Do I still hold to the dominant policy position of Western Europe that Putin poses a security threat? Again, I certainly do. But I’m learning to see Ukraine through the prism of history and now have a much more nuanced view of the country (more accurately cast as “the region”)—and its past. But this more refined view applies to Poland, as well, and to Russia itself. Much of this “attitude adjustment,” as it were, flows from a re-examination of Poland, Ukraine, Austro-Hungary, Russia and Germany (Prussia) between the Third Partition of Poland (1795) and 1945.

The simplest way to consolidate it for people only vaguely acquainted with the history and ever-changing political geography of that section of Europe is to describe it as the Hatfields and the McCoys to the 1,000th power. And just to make the process more bafflingly bloody is the over-arching role that anti-Semitism has played since . . . oh, pick a time, any time, going back to the reign of Catherine the Great and her decrees (1791 to 1794) that established the Jewish Pale of Settlement.

My example of Russia and Ukraine is only that—an example of a complex issue of broad public concern, no matter which side of the problem you find yourself, be it aggressive support or wholesale abandonment of Ukraine. Now move on to China; Israel and Gaza (and the West Bank); the flow of migrants from Latin America; the prospect of destabilizing migrations in other parts of the world, driven by climate change and failing agricultural prospects. Again—scratching the surface only to learn how much more surface there is to scratch before you get below the surface.

And so far here, the context has been “foreign policy.” What of all our pressing domestic issues? How do I scratch even a portion of any surface pertaining to housing, energy, infrastructure, public health, education, tax reform, the economy, and a hundred other serious matters that are out of sight, therefore out of mind until some crisis pushes them into view?

All of which is to say that by scratching the surface of Russian history, I’ve exposed my appalling ignorance about pretty much everything. It’s nearly enough to compel taking a sabbatical, joining a monastery and taking a vow of silence. But would that tame my opinionated tongue or do just the opposite upon my release?

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

1 Comment

I work with scientists, and if they ever happen to weigh in on something of broad public interest, I’d expect it would be in spite of, not because of, their deep expertise in certain aspects tumor cell biology. If I were president, I’d rather have you (or someone who read a summary of the Stalin volumes) as a foreign policy advisor than one who buried themselves in a decade of scholarship untangling the rivalries and foreign meddling in the latter days of the Kievan Rus.