APRIL 23, 2025 – We go through life taking lots for granted. In many respects, that’s okay. If we stopped at every turn to take full stock of the miracles in our lives, we’d make little progress in compiling additional miracles to take for granted. Furthermore, if we shifted our attention from pressing challenges and instead spent our waking hours admiring the miraculous, we’d soon be in a world of hurt, buried and flooded by our problems. Thus, I don’t advocate a whole paradigm shift from problem-solving to miracle admiration.

Nevertheless, in this time of regression—and I submit that future historians will label the current epoch as just that; of widespread political and social dysfunctionality—it is critical to draw hope and inspiration from whatever quarters we can. The good news is that the sources are everywhere. You just have to look . . . and listen.

This evening, after a review of the latest headlines reflecting a country in self-inflected distress, I watched and listened to a recording of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony performing Brahms Symphony No. 1 in c minor. I’ve heard this masterpiece of Brahms countless times over the years, and it will always be among my top 100 favorite pieces of orchestral music. You might say, however, that I’m so familiar with the symphony, I take it for granted. Moreover, because in technical and artistic difficulty it’s the musical equivalent of a double-black diamond mogul run at a premiere ski area in the Rockies, I’ve never heard Brahms First Symphony performed by a mediocre ensemble. I take for granted that when I listen to a recording of it, the caliber of the performance will be at the very least, of passing quality.

This evening, though, I paid closer attention than I have in many years—perhaps since I was a teenager, when I’d listen to the piece while sitting perfectly still with my eyes closed. As I experienced the piece this time around, I became intently intrigued by the many detailed layers of human interaction involved in bringing such magnificent music to life. In a word, I was flabbergasted.

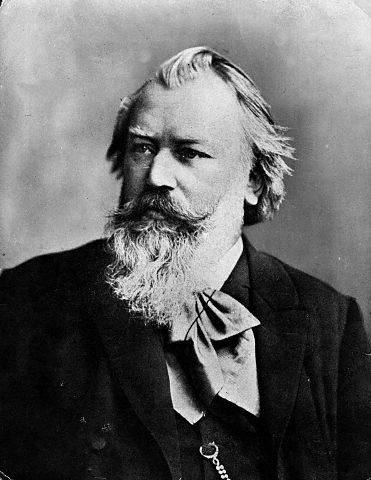

In the first place, there was Brahms the composer. Or more precisely, there was Brahms plus the many musical influences on his work—from contemporary ideas and instruction to all the musical precedents that informed Johannes Brahms and in one form or another, found renewed incarnation in his compositions.

Once he organized his ideas for the symphony, he used a well-established language of musical notation to put the ideas down on paper—fully scoring the symphony; that is, writing out all the parts for strings, brass, woodwinds and percussion.

But just as a book sitting on a shelf is dead to the world unless and until someone pulls the volume away from its companions, opens the cover and starts reading and apprehending what the author wrote, so is the manuscript of Brahms’ First silent until a group of proficient instrumentalists open the pages, read the musical notations and translate them into sound.

Of course, I’ve been to innumerable orchestra concerts. Back in the day, I actually played in such concerts. After a time, I’d taken much for granted—that the conductor knew how to conduct and ever more important, knew how to rehearse; that everyone in the ensemble was sufficiently proficient, technically and musically, to draw sounds out of an instrument; that they knew how to play together with the same level of precision and coordination that a surgery team deploys in operating on a patient. In the case of a Brahms symphony, the ensemble effect is a far greater challenge than it is with say, a string quartet or a solo violinist with a piano collaborator. On an even more granular level, each member of the orchestra must continuously alternate sight between music and conductor and work the left hand in close coordination with the right hand. Thrust into middle of it all is tempo, rhythm, timbre, intonation, dynamics, accents, and other musical features and nuance.

Pulling this off is nothing short of miraculous—bringing together a stage full of individual instrumentalists under the direction of a conductor, who then produce an intricate, 45-minute-long complex of coordinated and highly structured sound as expressed by the composer in the time-honored language of musical notation.

I felt my head spin as I took close measure of this extraordinary feat. To take it to the next level, I contemplated the sheer scale of the “miracle of the symphony.” Brahms wrote three more symphonies; Beethoven, nine; Bruckner, 11; Mahler, nine; Mendelssohn, five; Schubert, seven (plus the “Unfinished” (No. 8) and the “Great” (No. 9 – also unfinished); Sibelius, seven; Mozart, 41; Haydn, 106; Dvorak, nine; . . . and so on; pieces that have been performed and recorded thousands of times since they were conceived.

As much as I love and appreciate symphonic music, this evening as I contemplated just a smidgeon of it, I realized the extent to which I’ve taken it for granted. When I consider the amazing level of coordinated effort required to perform a work like Brahms’ First Symphony, I rediscover hope, even optimism, in humankind’s ability to recover from self-inflicted chaos. If the bad news is that we are superb at wrecking things, the good news is that we are equally capable of working in close cooperation to pull off miracles. I wouldn’t bet against our species yet.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson