MAY 22, 2023 – (Cont.) What amazed me as much as Carl’s steel driving skill was his ability to line things up so that the holes in the sides of the dock frames lined up perfectly with the holes in the pipe brackets. After Carl had driven the pipes down into the lake bed and adjusted the brackets, Dad and Grandpa slid the dock sections down the bank. Carl then muscled the heavy wooden frames onto the brackets, made some minor adjustments and called out for the bolts that would hold the frames in place. Dad then conceded to Grandpa the light task of fetching from the boat box up on level ground, an old, red, Hills Brother coffee can full of carriage bolts, nuts and washers. With a Rio-Tan cigar between his teeth, Grandpa handed the can down to Carl standing in the water.

Within minutes, all the bolts had been run through the matching holes in the frames and brackets. Carl then slipped the washers on and tightened the nuts. The dock was as solid as a concrete pier.

Next came the boat lift or what we called, the “cradle.”

Dad, Carl and Grandpa would be thunderstruck if they laid eyes on the solar-powered, 2,000-pound, gleaming, aluminum boat lift that is now installed where Carl used to “drive steel.” The first question they’d ask would be, “How in the world did you get it there?!” But I’m getting ahead of myself.

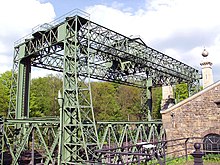

Way back in time, our boat cradle was a primitive precursor of its technologically advanced successor. However crude the original equipment, it would still function perfectly fine if a couple of people wanted to risk killing themselves assembling it. It consisted of two wholly independent, overhead sections, one for the bow and the other for the stern of a modest boat—in our case, a 12-foot Alumacraft. In its own fashion, the cradle was a clever piece of engineering.

Each of the sections was in the general shape of triangular Tobler chocolate package and housed a large roller with a large, cast iron crank attached. A rope with a clip on the end was wound around the roller of the front section, which you hooked to an eyelet at the bow of the rowboat. While standing on the dock next to the cradle, you could then raise and lower the bow by turning the crank one way or the other. Attached to the roller of the other half of the cradle was another rope, except instead of dangling straight down, it was looped so as to pass under the boat as you navigated into the cradle. Again, while standing on the dock, by turning the crank on that section clockwise, you could cause the rope looped under the boat to lift the stern out of the water.

Then came the clever part: a flat, L-shaped piece of steel attached to the back rope and fitted over the dockside gunwale of the boat. Once the bottom of the boat was about two feet clear of the water (you’d have to first crank the bow up to that height), you pulled a lever on the back roller, then crank counter-clockwise. The lever was attached to a long, angled metal catch, which snagged the rope and miraculously flipped the boat upside down. It was an ingenious system, and I never saw another one like it except at our closest neighbors, the Campbells, a few hundred feet down the shore.

If the cradle was clever, it was also crazy and potentially dangerous. In the first place, someone had to lift each of the two, clumsy, back-breaking sections straight up four feet to pull them out of the hinge-topped boat box, where they were stored between summers. Removing them from the box was always Dad’s job, and when Grandpa was out of earshot, Dad would mutter for the umpty-umpth time what a poor design that “doggone boat box” was. I knew by process of elimination that Grandpa had designed it. (By my mid-teens, when I was installing the dock and cradle single-handedly, I figured out a system for removing the cradle sections one end at a time, thus saving my back—and avoiding perpetuation of Dad’s criticism of Grandpa.)

But the great danger inherent in the cradle was quite apart from its weight and clumsiness. Grandpa had no greater concern in life, it seemed, than the threat the apparatus posed to our safety. He didn’t scare easily, and after all, I knew he’d been through a war, so I took him very seriously, as did my sisters, when he repeated his admonition about the cradle. He taught us well—until . . . one day there was an inexplicable slip-up. On that occasion I got to see exactly what he’d been warning about, and I made certain it never happened again, at least under my watch. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson