JULY 8, 2020 – Among my required triennial continuing legal education credits are two regarding “elimination of bias.” To satisfy this requirement I recently attended a webinar entitled, “The Impact of Bias in Negotiations and Mediation” by Nina Meierding, a nationally acclaimed expert. I hung on every word.

Back in the day, “old school” lawyers expressed a jaundiced view of the “elimination of bias” mandate. At best they ridiculed it as “stupid.” At worst, they viewed it as a left-wing conspiracy threatening their control of the world. That world has radically changed since “back in the day.” Many “old school” lawyers have graduated to grave or retirement. Those who remain are more conspicuously “old school” than their brethren were “back in the day,” the latter having benefited from wider “group camouflage.”

Whatever disposition the modern lawyer might have about such matters, that lawyer would be well served by listening carefully to Meierding’s presentation.

Nay, anyone in today’s world who forms opinions about other people would benefit greatly from Meierding’s insights. She begins with a quote attributed to Clyde Kluckholn, the American anthropologist and social theorist: “We are all like all others, we are all like some others, and we are all like no others.” On the heels of that, she adds her own statement: “A prototype should never be a stereotype.”

For two hours—no let-up—she describes how differently people view the world.

For example, she addresses “fairness” by describing four contrasting approaches to it: legal, equity, faith-based, and culturally- or needs-based. However you might define “fair,” if you’re judging another person’s definition, you need to understand what informs that definition—as well as your own.

Another example: monochronic vs. polychronic people, the former being far more structured and organized and the latter being less so. Not surprisingly, it’s easier for the polychronic person to adjust to the monochronic view than vice versa.

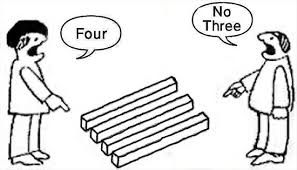

A further example: high vs. low contextual communicators. “Highs” use indirect messaging to make a point, while “low” context makes the same point directly—giving rise to misunderstandings when a “low” context person assigns the same approach to “hearing” as to “saying.”

Then we have “high” certainty avoidance vs. “low” and how these can be associated with various cultures. This difference becomes particularly critical in “nailing down details” (or not) and contingency planning in negotiations and contracting. Also—high vs. low “power distance,” meaning how different cultures/value systems approach formality, authority, obedience, apology, and privacy. What I found particularly intriguing was how differently people around the world determine “when a deal is a deal.” How often, I wonder, is “a liar” not?

Carefully avoiding value judgments, Meierding observed a central difference between the United States and the vast majority of the rest of the world: a highly individualistic culture vs. a more collective one. Awareness of this, she explains, can better inform how (prototypical) Americans perceive, respond to, and strike agreements with people from other parts of the world.

I now feel better equipped to observe and interact with the world.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2020 by Eric Nilsson