OCTOBER 3, 2022 – Today marks six weeks from “chemo-blast-off.” To celebrate, I took a long walk in nearby Como Park. As I admired the many trees that have become my friends, I contemplated the generations of park visitors who’ve also laid eyes on those oak, pine, maple, locust, chestnut, and cottonwood (to name a few) trees—and future generations of visitors who will do the same.

Each tree, like a human, will succumb to the rigors of time and commit its soul and splendor to the hereafter. This somewhat morbid thought made me recall an adage attributed to the ancient Egyptians: “A person dies twice; first when physical death occurs and again when the person’s name is no longer mentioned.” In the case of a tree in the park, the “second death” transpires long after trunk and branches are hauled away; when the stump is atomized by decay and becomes one with the soil. By then, no one will remember that an oak, pine, maple, et cetera, “once stood here.”

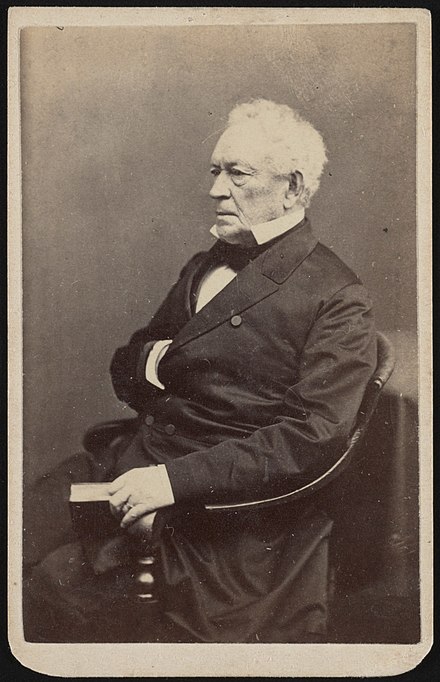

These thoughts reminded me of a line from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.” That statement, in turn, made me think of Edward Everett, the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, held on November 19, 1863—slightly more than four months after the turning-point battle of the Civil War. Everett spoke for two hours; Lincoln, for two minutes. Contrary to Lincoln’s declaration, the world has long-remembered what he, Lincoln, said there, but true to the same line, no one long-remembered what Everett said in his marathon address.

I later researched Edward Everett. I had a head start, thanks to my dad, whose library included a volume of speeches by the “Man from Massachusetts,” famous for his grandiloquence. When I was a fifth-grader, memorizing the Gettysburg Address, Dad informed me of Everett’s long-forgotten speech given just ahead of President Lincoln’s masterpiece of oratory.

“Edward Everett.” How many people of today’s world have heard of him? Under 0.1%? Yet, by any standard, he was a prodigy, an academic titan, and a renowned public figure—Congressman; governor of Massachusetts; president of Harvard; Secretary of State; Senator; vice presidential candidate (Constitutional Union Party – 1860)—however misguided he was initially about compromise with the South to avoid a civil war. (He “got religion” after the Confederate States of America gave the Union the middle finger and unleashed a torrent of cannon balls at Fort Sumter). Everett contributed mightily to the life of the nation, but if he hasn’t died his “second death” quite yet, chances are he’ll “go” long before Lincoln does.

Ironically, Everett’s 13,000-word speech at Gettysburg made many detailed references to the Periclean Age, yet it was Lincoln, who, by his brilliant oratory (his Gettysburg Address was 272 words) and leadership, became the American Pericles in our Pantheon of Heroes. To Everett’s credit, however, on the day following the dedication, he wrote to Lincoln, “I wish that I could flatter myself that I had come as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

By this post, may Edward Everett stay “alive” a tad longer than would otherwise be the case. And may my favorite arboreal friends of Como Park outlive us all, even should the youngest among us live to 100.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson

4 Comments

If you haven’t read it, I recommend “The Hidden Life of Trees” by Peter Wohlleben

Deb, I’ve read it and found it inspirational; it’s on the “re-read” pile, too! Glad you’ve read the book and that you found it rewarding. — Eric

Everett’s reply to Lincoln the day after the addresses was spot on. Good for him to recognize that.

I thought so too. Plus, he wasn’t afraid to change his mind about compromising with the South. He went from opposing Lincoln in the 1860 election to becoming the president’s champion. — Eric

Comments are closed.