MARCH 19, 2022 – In plotting my “Grand Odyssey,” I considered three objectives: 1. Natural wonders (e.g. New Zealand; the Himalayas); 2. Exposure to an intensely alien culture (e.g. India; Egypt); and 3. Life inside the Soviet Bloc.

My interest in the Soviet world dated to my improbable encounter with Pavel Šebesta at a hostel restaurant in Delphi, Greece in 1979—apogee of my Eurail trip covered in “Hellas Redux” (see 3/8/22 post). Thanks to his command of English and sense of humor and our common interests—art, music, skiing, travel, history, politics—we enjoyed a lively conversation far outlasting posted dining hours. As a citizen of the Soviet Empire, Pavel of Prague was like some exotic creature escaped from a high-security zoo. Yet, at the same time he seemed like a close, long-time friend.

With his parents and sister guaranteeing implicitly his return to “prison,” Pavel had obtained the necessary exit visa for travel to the West. Free in Greece to speak his mind, he did, and in describing life under Communism, the Prague Spring, and the Soviet invasion that quashed it, Pavel fired my curiosity about the world behind the Iron Curtain. He also talked about his family—his father, an artist; his mother, who worked at a foreign language bookstore; his sister, a talented student—and his own studies in medicine and residency in heart surgery. A Renaissance man, Pavel had the talents to be a star in many endeavors, but in frustration he remained a prisoner of the East—albeit on temporary parole.

Our conversation continued via (censored) correspondence (and continues—uncensored—today). He regularly renewed his initial invitation to visit him in Prague. In planning my “Grand Odyssey,” I not only accepted his invitation; I expanded it to other countries of the “Soviet Bloc”—including the USSR itself.

Plans were laid. From Belgrade, I’d take a train to Budapest—my first exposure to Pax Sovietica. After several days in that historic city, I’d aim for Prague.

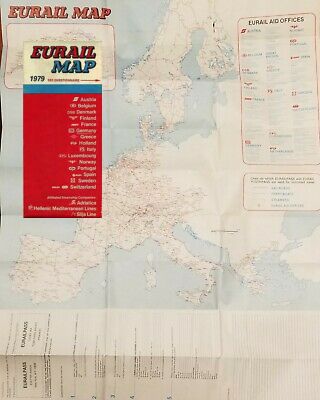

Neither Budapest nor Prague had appeared on my 1979 Eurail map. In fact, everything east of the Iron Curtain was depicted in solitary gray—no national boundaries, no capitals; nothing of the Soviet world. Americans and their European allies called it “Eastern Europe.” From my first encounter with Pavel, however, he instructed that this nomenclature was off the mark if not offensive. “Look at the map of Europe,” he said, “from the Iberian Peninsula to the Urals. Prague is not ‘east.’ It’s west of Vienna, at the very center of Europe. It was the capital of the Holy Roman Empire!” (In Poland I’d encounter a variation of Pavel’s remarks. As one Pole explained, “Draw one line from Nordkapp—the northernmost point of Norway—to the toe of Italy and another line from Lisbon to Moscow. The lines intersect over Poland.”)

When my train from Belgrade reached the Hungarian border, guards, and guard dogs, I thought about that Eurail map. I was about to enter the “gray zone”; I was about to go off the map.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson