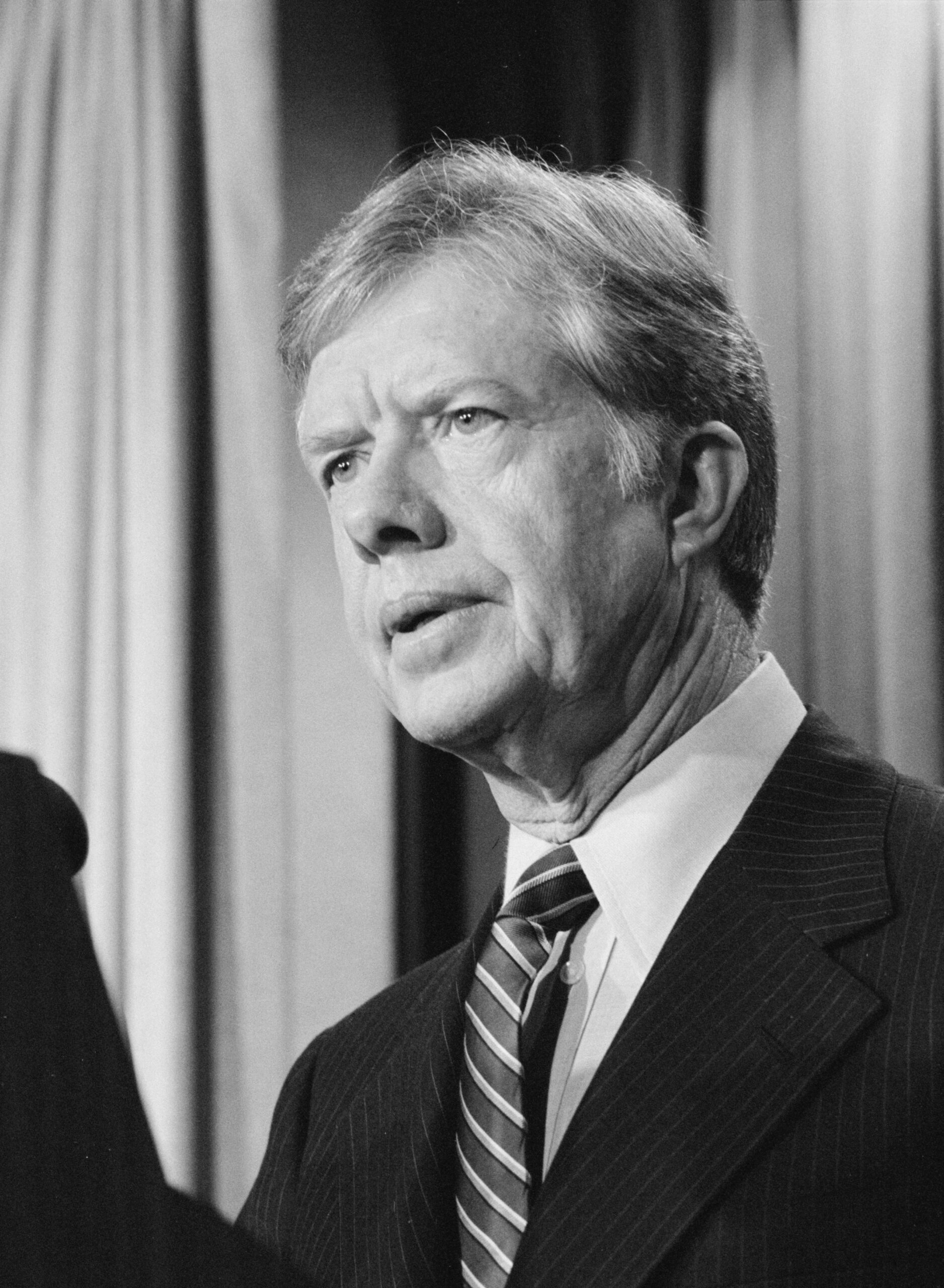

DECEMBER 30, 2024 – President Jimmy Carter was such a nice guy, people said so long before he died at the ripe young age of 100. As people reflect on his exemplary life, I have a few memories of my own about him.

The first was the mock Democratic Presidential Nominating Convention held at my college during spring semester 1976. Several classmates of mine spearheaded the project and recruited me to head up the “Humphrey Campaign.” In real life at the time, Humphrey seemed to be in the lead for the actual nomination, so my role was considered significant by the group in charge of the mock exercise. The student delegates, however, had different ideas. A groundswell of support developed for the “peanut farmer from Georgia.”

I’ll never forget the panic in the voice of the mock convention leader when he met with me about it. “We can’t let Carter win!” he said. “I want to make sure our [mock] convention gets good publicity beyond campus. I want the whole country to know that we ‘got it right’; that we ‘called it’ before the Washington and Lee convention even takes place.[1]”

My “job” as Humphrey’s campaign chair increased in importance. After waging a frantically ambitious lobbying effort, we convinced enough “Carter delegates” that given how important it was to choose the candidate who in reality was most likely to win, they should switch to the Happy Warrior. To our great relief, they did and Humphrey was the victor at our mock convention.

We were all forced to eat cake, of course, when a few months later, Carter won the actual nomination. Chagrined, we who’d pressed for a Humphrey victory realized we should have listened to all those “Carter delegates.” They were way ahead of the conventional wisdom: Carter was a “new and improved” candidate who deserved to be president.

My second memory about Carter occurred 15 years later. I was a fellow of the Mondale Forum at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. During one of our small group sessions, the former vice president himself led a discussion about the clash between politics and policy goals. He told a number of inside war stories about the Carter Administration. My group found these fascinating. Here was the ultimate insider telling us what transpired behind the curtain.

What I remember most clearly about Mondale’s account was his express frustration with Carter’s unbending idealism. On one level Mondale admired Carter’s ideals because in large part, Mondale shared them, but on a practical level, the vice president thought that Carter’s insistence on policy purity was the enemy of the “good,” with the consequence that much of Carter’s legislative agenda met with failure. The president refused to “play politics” with powerful members of the House and Senate and thus failed to muster critical support for important legislation.

At the time I had not yet read Robert Caro’s definitive biography of LBJ. When I finally did, many years later, I understood much better Mondale’s criticism of Carter. LBJ himself would have run circles around Carter and expressed judgment far harsher than Mondale’s. By almost any gauge, LBJ’s legislative victories eclipsed Carter’s record, leaving for us to debate, what makes the “greater” president—a guy (LBJ) who bends and twists, lies cheats and steals but in the end, get things done because he knows how to manipulate powerful people OR . . . a man (Carter) of impeccable morals, free of all scandal, unwavering in his principles, but because of his moral and intellectual integrity and refusal to smoke cigars and drink brandy in back rooms, calls for perfection and loses the “good”?

Carter’s steadfast adherence to human rights in formulating and implementing foreign policy disrupted long-standing American support of dictators and oppressors who, nonetheless, supported American interests. Unfortunately and ironically for Carter, it was his support of the Shah of Iran that led to the president’s biggest catastrophe—the 444-day hostage crisis in Tehran. But the Camp David Accords bringing an improbable peace between Israel and Egypt was a brilliant victory for all parties concerned. Carter took a huge political risk in his pursuit of peace—an act of courage that speaks volumes about his character—yet it was such exceptional character that gave Carter the ability to succeed where so many before him—and since—have failed.

If Carter can be criticized for not having had the temperament for compromise in the rough game of politics—“the art of the possible”—he should be admired for having principles and adhering to them even if to a fault.

My third memory of Carter was his “Malaise Speech” in July 1979. I remember distinctly the reaction that it evoked at the time. “What!” critics would say. “The president is telling us how bad we are? He’s supposed to be giving us a pep talk, and instead he delivers a real downer speech.” I must confess that to a large degree I shared that response. Yet when I reread the speech today, I’m struck by Carter’s brutal honesty and sincerity—qualities to a degree we haven’t seen in any of his successors but one. I’m also impressed by the extent to which that speech describes America today, over 45 years later. If every citizen today would benefit from the speech, I can’t imagine it being delivered by the sitting president or the president elect.

We’ve lost a truly great man if not necessarily the greatest of presidents—according to conventional wisdom to date. But maybe in time that conventional wisdom will shift. If character during Carter’s term in office diluted his political effectiveness, character today has been rendered irrelevant. This present reality begs the question, “Can a president of impoverished moral character bring more benefits to the nation than Carter delivered?” And perhaps more important, “In the long run, how do we wish to be defined—as people of good character who choose leaders of good character or people for whom character doesn’t matter, in which case we will be led by people who lack character?” Maybe the deeper we wade into political territory in which character is irrelevant, we will discover that the opposite is true after all. The essence of Carter’s legacy will then come into full view, and his standing among his predecessors and successors alike will improve significantly.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1]For many general election cycles Washington and Lee University had conducted mock nominating conventions and had a near perfect score in predicting the nominees. Our guy wanted to make a name for himself by beating Washington and Lee to the punch.

2 Comments

Glad I walked with you today. Now I have a new viewpoint to read daily.

Bruce, you found the site! Glad to see you aboard.