MARCH 18, 2025 – Yesterday evening in the company of my two history-hungry friends, I attended yet another amazing two-hour lecture (no breaks) by the inimitable Russian history scholar, Professor Theofanis Stavrou. With his usual enthusiasm he delivered his far-reaching deep-diving tightly organized well-sourced exposition. His notes were on the lectern, but he never consulted them. His uber-command of the subject matter left us breathless. Along the way, he commended to us numerous books beyond the exhaustive reading list that accompanied the course outline. I realized that if I were serious about swimming in the deep end of the pool of Russian history, I must step up my reading.[1] It wouldn’t hurt to search for, find and drink from the Fountain of Youth that I took so for granted during . . . my youth. Reading requires time, and youth is time.

Yesterday’s lecture covered the time period from 1881—the year in which Tsar Alexander II was assassinated—to 1917, the year of the February Revolution, in which the Tsar (Nicholas II) was toppled, and the October Revolution, in which the people who’d deposed the Tsar were themselves chased from power. Professor Stavrou’s theme was “Russia in the twilight,” by which he explained that twilight means the period of light between darkness and sunrise, as well as between sunset and darkness.

The Revolution of 1905 forced concessions by Nicholas II, including creation of the representative Duma (parliament), which convened four times before the catastrophic upheaval triggered by the Aurora.[2] Under the stewardship of the pragmatic, forward-thinking finance minister, Sergei Witte, Russia had begun to modernize. Before the October Revolution, was Russia heading toward the light or the dark? We all know the ultimate direction, but in retrospect, was the route to Leninist authoritarianism, then Stalinist dictatorship inevitable? Advanced scholarship might provide a definitive answer for some students of the period, but as with most things, absolute proof of one immutable conclusion or another eludes us.

As I later reviewed my jottings during the lecture, looked up some of the books Professor Stavrou had recommended, and contemplated his remarkable survey and analysis, I gave thought to his question—the direction of “Russia in the twilight.” I considered the parallel regarding our own country in current times. If we too are “in the twilight,” are we headed toward light or darkness?

Russia in the late 19th century/early 20th century, of course, bears little resemblance to America more than a century later, but when you subject any society—past or present—to close analysis, you become entangled in a host of interactions. What you learn in the case of any historical study is that multiple factors influenced outcomes. The challenge is to identify all those influences, explore their nature, and weigh their effects. Skill and experience in approaching historical problems and questions can be applied with equal gain to improving one’s understanding of current conditions and where they might lead.[3]

To help us examine the question in the context of late 19th century, early 20th century Russia, we were introduced to an array of factors, intermingled by actions and inaction. Sergei Witte, for example, advocated construction of railways to connect a vast nation that in area was the largest of Europe, as well as of Asia. Railroads were essential to the exploitation and transport of natural resources and formed the backbone of a society transitioning from nearly wholly agrarian under autocratic rule to somewhat industrialized under emerging democratic possibilities—an ostensible path toward “lightness,” at least by the measure of the liberal democracies.

What could go wrong? For starters, the growth of cities around the new factories fed by the new railways. Who would the workers be? Oh yes—inflows of migrants from the hinterlands, peasants all. How would they be paid, housed and fed? All in conditions that were grand petri dishes for revolution. And what about capital? A country full of peasants and a tiny slice of unproductive nobility had little to contribute, so the search for loans and equity capital led abroad—mainly to France, as it turned out. Politics followed money, and the inflow of investment from France was followed by the Dual Entente.

Now enter the Great War—triggered by the assassinations in Sarajevo but blown into the worst conflagration the world had ever seen . . . because of Big Power alliances such as the one between France and Russia. The conflict sucked so much blood out of Russia the fledgling government couldn’t withstand the domestic revolutionary pressures. The rest is . . . (more) history.

My main high-level takeaway from yesterday evening’s lecture, however, was the fact—the down and dirty FACT—that the more I study Russian history, the more I realize how much more I need to know in order to understand. And if Russia is a critical player on the stage of contemporary affairs of the world, what about China? India? Brazil? The whole of Africa? The whole of Asia, South America, Europe? And what indeed about our own country? Whether we’re in steep or shallow decline; engaged or isolationist, our status will have major repercussions round the world. How now to know and understand all that needs be known and understood?

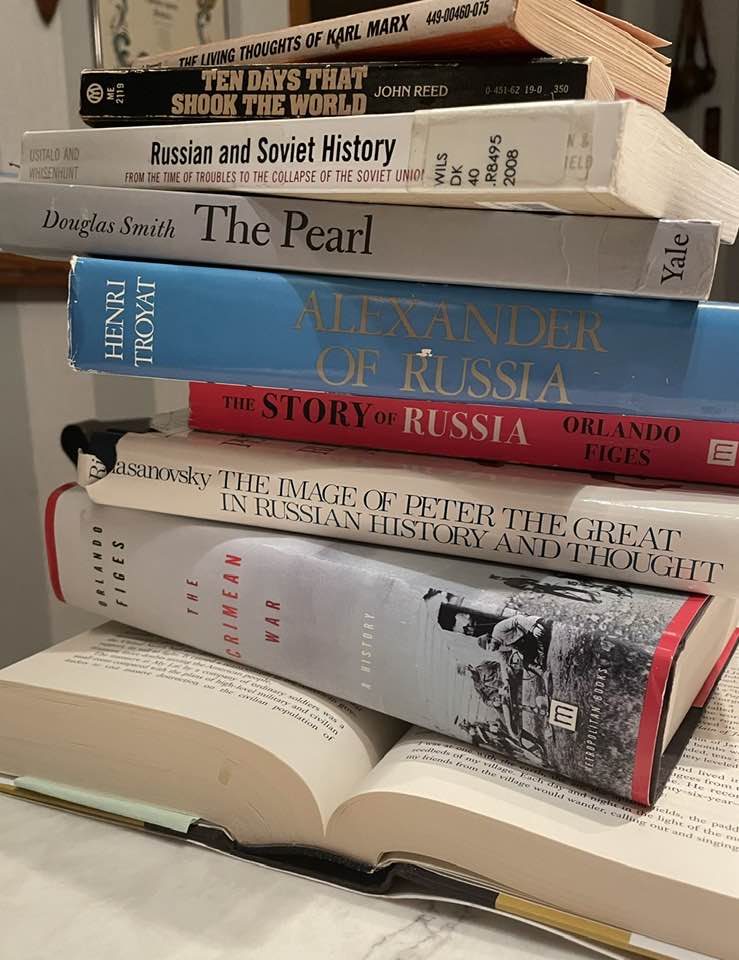

My fate is to be forever the student—and in search of the Fountain of Youth. Bring on the books.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] About halfway through the lecture, Professor Stavrou noted that the bibliography on the Russian Revolution alone included over 6,000 books—excluding languages other than English.

[2]The Russian navy cruiser moored on the Neva in St. Petersburg. The crew fired blank shots to signal the start of the Bolshevik takeover.

[3] It was long in vogue to say “history repeats itself”; therefore, we should know the past so we can avoid the repetition. That has since been supplanted by the cliché that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes,” which is merely a refinement of “history repeats.” In any event, the central benefit of studying history is learning to identify and understand causal relationships and to improve understanding of how the world in which we live came to be and how we might influence for the better its future course.