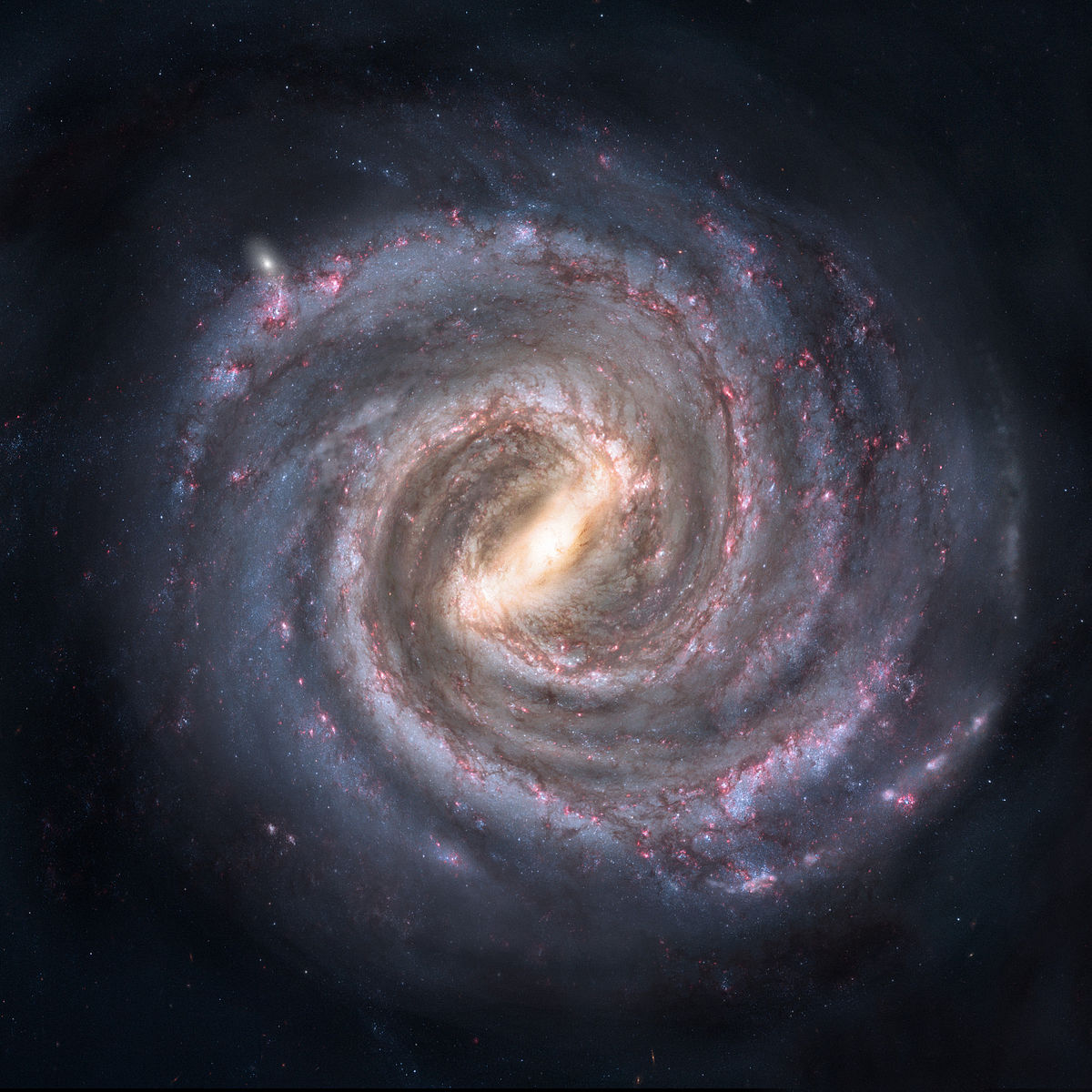

MARCH 17, 2025 – What a difference a day makes. A day; one full rotation of planet Earth, as it revolves around a star, which, in turn, with its eight captive orbs whirls around inside an arm of the galaxy, which itself is soaring through space too vast for our imaginations to grasp. But I’m getting light years ahead of myself.

Back to the “difference a day makes.” Last Friday we on this part of the planet enjoyed a precursor of better times ahead: full-on spring. Yet, given the overall warming trend of the earth, perhaps those better times are the opposite. Maybe we’re the frogs in the proverbial pot of cool tap water sitting atop the stove burner. Sure, the water will be turning more comfortable as its temperature rises from subterranean “cool” to room level ambience. But unless the pot is removed or the burner heat is reduced, we’ll soon be not-so-comfortable, then hot, then boiled.

Oops! From “getting ahead of myself,” I’ve turned into a frog in pot of water on a hot stove . . . except on the very next rotation of the planet, when we Minnesotans ventured outside we found ourselves back inside the snow globe of winter. The mercury, so expansively happy the day before had now compressed its molecules to register below the freezing point of water. A fierce wind blew down from arctic regions, bringing with it icy precip, including flecks of snow, which threatened to organize into measurable accumulation.

I suited up and took my power walk to “Little Switzerland,” where the last remaining snow fields had been savaged by the unseasonable warmth of the day before. With fingers curled up in a defensive position inside my winter gloves, I shortened my neck the best I could to settle my jaw bone into the collar of my down jacket—as if my head were a big fat bird seeking the warmth of its nest. When my route turned into the cold mean breath of Borealis, my eyeglasses reminded me of the upper panels of a gondola car at a high mountain ski area caught in the jaws of winter. The misanthropic wind-driven sleet pelted the outside of the “cable cabin” that carried me high up the mountain. If there was a scenic view to be enjoyed in more agreeable conditions, I saw no hint of it, as the fog on the inside of my “gondola” eyeglasses further obscured conditions on the “mountain.”

Atop “St. Moritz,” I imagined arriving at the summit station. To effectuate my exit from the gondola car I removed my sleet-covered eyeglasses but with little improvement in visibility. After casting a glance down the windward side, I elected to “ski” down the other. I allowed myself a touch of reverie in the knowledge that I still “owned” the slope—as I had nearly all winter long.

On the way home through “Austria” and into “Bavaria,” I returned my eyeglasses to my face and leaned into the sting of icy grit driven by frosty gusts. To distract me from discomfort, I thought about the bigger picture—earth from the vantage point of the moon. Would I be able to observe our planet’s rotation? After all, I knew, the surface was moving at the rate of just over 1,000 miles an hour—right around the speed of sound, though I wondered what adjustments needed to be made based on wind and air temperature.

This elementary calculation (based on 24 hours in a day and earth’s circumference of 25,000 miles) led me to wonder—what then, was the speed of earth’s revolution around the sun? I knew our distance from the sun (93 million miles), so in very rough terms, the total distance of our orbit would be 2𝝅r—or roughly double 3.14 x 93 million, call it 2 x 280 million miles = 560 million miles—except, I recalled reading somewhere that “our” orbit is slightly elliptical. The objective, however, was simply general distraction, not mathematical precision, so somewhat arbitrarily I tacked on an extra 10 million miles for a total orbital distance of 570 million miles.

Next, I had to calculate the number of hours in a year. From my days with “the big law firm,” where one’s worth was measured by one’s billable hours, I knew there were 8,760 hours in a year. That was the theoretical maximum number of hours that could be billed in a year—unless you were double billing, which, it came to my attention, some lawyers did, in which case infinity was the theoretical limit.

With D (570 million) and T (8,760) in my head, all I had to do was divide D by T to reach the velocity of the earth as it runs around the sun each year. For ease, I rounded the 8,760 hours up to 9,000 and lowered the 570 million miles down to 560 million. Running this simplified division problem through by frozen brain gears took longer than it would at say, sea level at room temperature. After half a neighborhood block, I teased out a range between 60,000 and 70,000 miles per hour. This effort took me around the final corner onto our street and down the block to our house.

Once I’d removed my gloves and uncurled by frozen fists under a stream of hot water over the kitchen sink, I repaired to the living room, where I fact-checked my guestimate for the velocity of the earth’s revolution around the sun. According to the internet, our speed is 67,000 miles an hour, which put me just past the middle of 60,000 to 70,000.

I then carried the process one step further: speed of rotation of the Milky Way. In a flash the internet told me that the site of our solar system spins at the rate of 130 miles per second—or 468,000 miles per hour. This leaves one remaining speed question: the velocity of the Milky Way as it soars through space. Ready for this? Yes? Think again. I don’t think you are. Not really. The answer is 1.34 million miles per hour.

The bottom line, I decided, was this: If the daily political news leaves my head spinning, I can just as easily spin it the other way by the combined velocity of [earth’s rotation =] 25,000 mph (earth’s rotation) x 67,000 mph (earth’s revolution) x 468,000 mph (Milky Way’s rotation) x 1.34 million mph (rate of expansion of the universe) = over a trillion miles per hour (versus the speed of light, a mere 670 million miles per hour).

It was all a good exercise in perspective: if our news feeds tell us that “things are changing way too fast,” some simple astronomical math says “maybe not so fast.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson