OCTOBER 13, 2024 –

Every good war movie—or just to be clear, “every war movie that’s a good movie”—winds up being an anti-war movie. Even a good movie about the “Good War” (WW II) is a reminder of the insanity and futility of war. By that I don’t mean that war is nugatory for the victors. The war effort was hardly so for the Allies in WW II: it resulted in the unconditional surrender of Germany on May 8, 1945 (V-E Day) and of Japan on September 2, 1945 (V-J Day). The flip side of those totally non-futile victories, however, was the total defeat of Germany and Japan—defeat that rendered the Axis war effort totally futile. Since in the end they would lose everything, why did they have to commit so many atrocities and unleash such attendant horrors? To satiate an unquenchable thirst for cruelty?

My second comment about the Good War is that movies about it have flooded the film scene for generations. Every possible angle of that war, it seems, has been captured by one movie or another, American or “foreign.” Thus, how is there room for yet another World War II “picture,” (as movies were called by the Greatest Generation back when they were earning that reputation)?

Yet, ample time should be made by modern movie-watchers to see April 9th, available on YouTube. A Danish production released in 2015, this simple film depicting the German takeover of Denmark on April 1940—barely seven months after the start of World War II—is a relatively low-budget but very high-quality work.

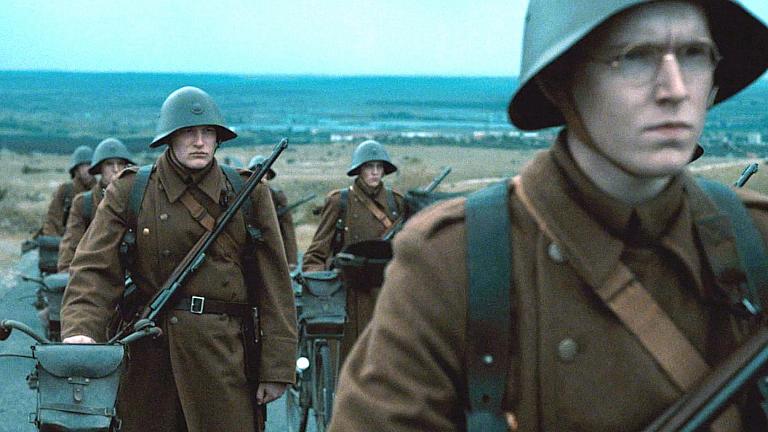

By way of background, bordering the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, diminutive Denmark with its ill-equipped military stood little chance of resisting successfully an invasion by the Wehrmacht, at that point by far the most powerful military machine in the world. April 9th captures this contrast in military realities by featuring the Danish force charged with holding off the Germans at the border: a squad of fewer than 10 with bolt-action rifles and riding one-gear bicycles . . . versus automatic weapons, panzers and other motorized attack vehicles. As the Danes await reinforcements that never appear, they put up a brief but valiant fight—which turns out to be worse than futile.

The film excels in two key respects. First, it gives the viewer a window into war at its most basic level: a bunch of callow soldiers, barely old enough to shave, with little training and outdated equipment and precious little ammo (40 rounds per soldier as they’re sent into action). Apart from some target practice, at which one of the boys doesn’t perform very well, the main drill is changing a flat (bicycle) tire, with the drillmaster barking an order to get the time down to 90 seconds. As you land in the middle of bickering in the barracks over whether the bad shot among them should hand over all or at least some of his allotted ammo to the best shot; as you see the fear in their faces; as you look over the shoulder of a young soldier as he peaks around a corner and sees a panzer rumbling up the cobblestones in the center of town, ready to unleash shells and a hail of bullets at everything and anyone in the way; as you experience the sheer terror of the group with their arms raised and shouting “Nicht schiessen! Wir kapitulierien!” (Don’t shoot! We capitulate!) as they face an overwhelming force of trigger-happy German infantry . . . you can feel yourself slipping into the socks, if not the shoes, of the young Danes, who are clearly no match for the Germans.

The second central feature of April 9th gets back to the futility of the vanquished—writ large on the canvas of what happened to this squad from the Bicycle Company. After withdrawing from the border area, the bicycle boys are ordered to join the garrison defending a town 10 or 20 kilometers away. The Germans are right on their heels, however, and before any kind of broader defense can be organized, the squad members take position up the street from where the bad guys will enter. With their bolt-action rifles the Danes do the best they can, but soon they’ve spent their ammunition. After losing a couple of young men (but taking down a number of Germans), they find themselves backed into a hopeless corner with only a handful of bullets left.

Repeatedly men call out “What’s your order?” to their courageous and sensible commanding officer, a young 2nd Lieutenant, who, having done well so far, is now at a loss, all options having been exhausted except . . . surrender. This decision elevates the intensity. Capitulation doesn’t guarantee that the ruthless, hair-trigger Germans won’t decide to shoot their defeated foes.

One of the Danes speaks German and is asked by the DanisH commander to translate for the latter and the German commander—a guy about the same age as his young Danish counterpart. You imagine the German as a guy barely out of high school . . . and from two towns over. Though hardened by training, the German nevertheless comes across as an honorable soldier. You assume that the captured squad will be treated as POWs, but in fact, the German commander is simply loading them up the defeated soldiers onto a commandeered city bus and sending them back to their barracks. He offers the 2nd Lieutenant a ride in a German staff car, but the Dane declines. “I’d rather ride with my men,” he says nobly and not surprisingly.

But then comes the tragic surprise. The German commander asks the Dane why he and his men shot at the Germans as the latter entered the town. The Danish officer reacts with puzzlement. “What do you mean?” he asks through his translator.

“Your government has surrendered,” the German says.

Because communications had been severed, the Danish squad had not been informed of the government’s surrender six hours earlier. The fire-fight—and the consequent loss of life—over two or three blocks of cobblestones had been wholly unnecessary. As this revelation crushes the soul of the Danish commander, it also exacts an emotional cost on the modern viewer.

I highly recommend this (anti-war) film for its script, casting, acting and direction. It tells a war story that is uniquely Danish and conveys it with stark simplicity. As far as I’ve researched the question, the movie stays true to the actual events it depicts.

Post Script: Denmark would survive its capitulation by relatively lenient treatment at the hands of the Germans as long as the Danish government maintained neutrality and acquiesced in German rule. By 1943, however, resistance and sabotage prompted the Germans to order a crack-down. In late September 1943, deportation of Denmark’s 7,700 Jews was announced—though news of the order was leaked in advance by the head German in Denmark at the time, Werner Best. Ordinary Danes launched a remarkable effort at great risk and danger to save their Jewish population, with 7,200 being spirited to safety across the waters to nearby neutral and unoccupied Sweden. The Germans rounded up and deported 500 Danish Jews to Theresienstadt, 90% of whom would survive their ordeal.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson