JANUARY 28, 2023 – For many years I encountered no clients, lawyers or other parties whose mother tongue wasn’t English. Oops. I must amend that. There were two brothers with whom I tangled; real estate developers of Venetian origin, who spoke Italian first and English second—or maybe it was fourth or fifth, given their cosmopolitan backgrounds in the tradition of Venetian merchants of the Renaissance. Their strictly Anglophone lawyers, however, were born in Minnesota.

Other than the Venetians, no one I encountered in my work zone spoke with a “foreign” accent—not counting Minnesota’s Iron Range mode of pronunciation. On rare occasions, I’d run into a lawyer originally from “out East,” who by some strange lottery had attended the University of Minnesota School of Law and never found his way back. I remember one in particular, whose Brooklyn accent was the source of great amusement, if not derision, behind his back. He was brash, but I felt sorry for him—the proverbial fish out of water, or rather, the “saltwater crab” swimming with walleyes. To improve my rapport with him, I once mentioned that my mother was originally from New Jersey. In the embarrassing silence that followed, I detected a smirk at my Minnesota naiveté.

Fast forward to now. Long gone from the corporate scene, I work on small commercial deals—real estate, mostly, with periodic buy-sell transactions involving fledgling, closely held entities. Thanks to repeat referrals, my deals involve players new to America and Minnesota. If they’ve had to adapt, so have I.

I don’t speak any East African tongues or languages of India and Pakistan, but at least I’ve become fluent in heavily accented English. Some parties have a total command of English, but often players have little to none, in which case my “accent fluency” is useless. The easy ostensible solution is through an interpreter, but often things “get lost in translation.” I have to pay close attention to word choice and idioms. Out the window goes a lot of “legalese.”

The bigger challenge, however, is conceptual. Voltaire said, “When it comes to money, all men are of the same religion,” but when it comes to American money law (i.e. business law), people involved in my work are often from the other side of the planet, so to speak.

This all requires patience, but in a long-standing tradition, people wanting to improve their lot in a new world are singularly impatient. Frequently, they don’t appreciate that a handshake plus a “contract” pulled off the internet and signed on behalf of a non-existent “corporation” won’t cut it in a system of complex rules, laws and procedures created and administered—some people would say, rigged—by a vast web of . . . lawyers.

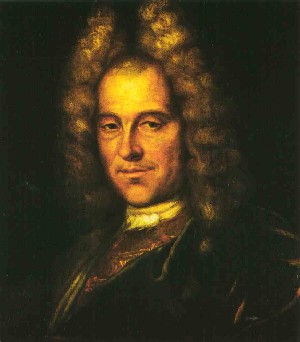

I sometimes imagine American jurisprudence as a Baroque palace on the outskirts of Vienna. The schloss is occupied by people running around in frilly, period attire, bowing, curtsying and most important—dancing to the music of the palace orchestra playing the latest output by Johann Joseph Fux*. Everyone speaks the same language until a new group shows up from parts East. With no advance training or exposure to the arcane protocols of the palace or customs of its inhabitants, the “uninitiated” newcomers are interested only in the pantry stock. Having fought through hell and high water across the steppes, their focus is on food, not silk stockings or esoteric dance steps.

The trick for us of the Baroque schloss is to adapt . . . by mentoring, adopting patience and thinking flexibly within the general construct and architecture of the ol’ palace.

* (1660 – 1741) Austria’s most important composer of the late Baroque period.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson