MAY 6, 2022 – Across my many conversations with Russians aboard the train, I endeavored to find consensus about one subject or another, such as national self-perception, for example, and impression of the United States, and most sensitive at the time—attitudes about the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. One person’s opinion is only a data point, but when you hear the same response repeatedly from everyone you question, you begin to detect a trend.

I was struck by the unanimity that developed around the question of Afghanistan. In every conversation on the subject, I used the same approach, asked the same questions, received identical answers. The survey went like this . . .

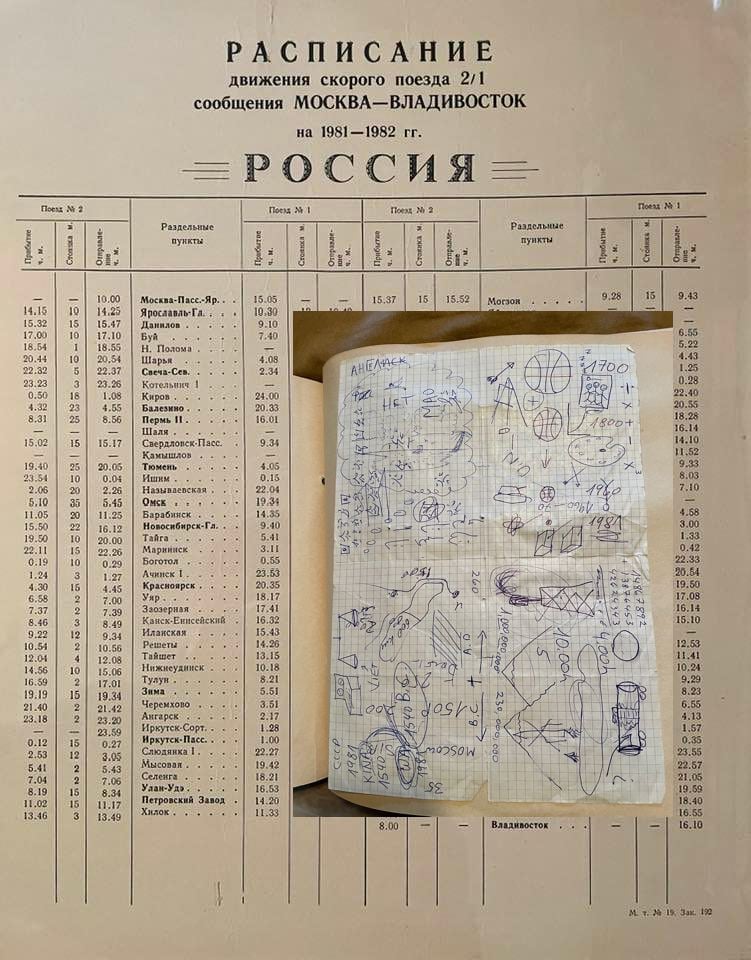

First, using “conversation sheets” (paper) I’d draw a line, write “Россия” (“Russia”) on the right (east) side, “Finland” on the other, “1939” and arrows running from the Russian side to the Finnish side of the line. (If there was any confusion on the part of the Russian(s) in the conversation, I’d refer to my pocket atlas of the world.) The final stroke, then, was a big question mark to connote, “Why did your country invade?”

In every single case, the Russians would repeat the party line: “First, Finland had attacked Russia.”

I took a similar approach to the uprising in Hungary in 1956; the rebellion in the DDR (East Germany) in 1953; the Berlin Wall in 1960; the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968. In every case, Russia (the USSR) was simply “defending itself.” I didn’t react to this blanket rationalization.

Then came Afghanistan. Again, the responses were unanimous—except . . . they definitely weren’t parroting the “party line.” Every Russian to whom I put the question—“Why did the USSR invade Afghanistan?”—the person would say, “США [“USA”]—Vietnam; CCCP [“USSR”]—Afghanistan.” Less than two years into its 10-year fiasco in Afghanistan, Russians were already viewing that quagmire as their “Vietnam.”

On the question of national pride, I also encountered broad consensus. Nearly every Russian whom I engaged in conversation beyond the exchange of pleasantries would ask me if I’d read Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, et alia, and when I replied in the affirmative, they’d ask about “other Americans,” and a number of Russians even asked me if “[our] schoolchildren read Tolstoy [et alia]”—whereupon I’d have to equivocate.

Along with pride in their national literature, the Russians I met aboard the train harbored a deep sense of collective suffering, most notably in what they called the Great Patriotic War (WW II). That enormous catastrophe unleashed on their soil left its inter-generational mark, and the subject arose as often as mention of Russia’s literature tradition. The topic was often initiated by the question, “Do you know how many of our people died in the war?” When it was first posed to me, I made the mistake of stating the number I’d learned in a(n American) college history class—16 million. I was immediately corrected (20 million*). When subsequently confronted with the question, I was able to appear “better informed.” (Cont.)

_____________________________

*This figure, even, is conservative. The total deaths, military and civilian, from all war-related causes is heavily disputed but by some estimates was as high as 27 million.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson