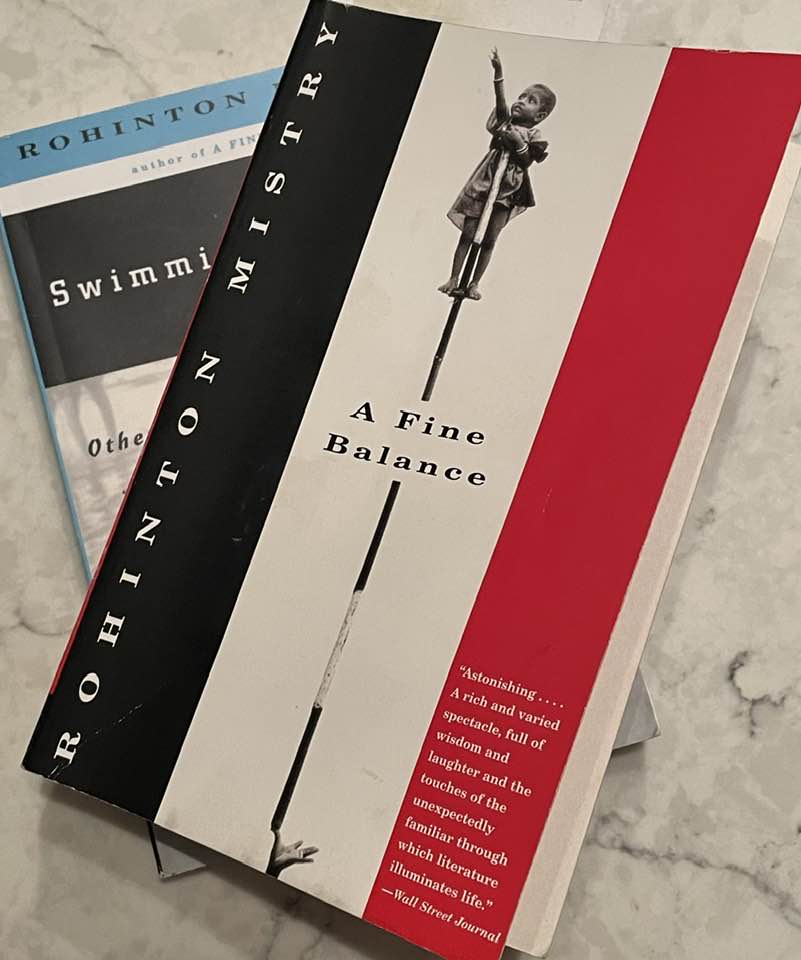

SEPTEMBER 27, 2024 – In late August, Lin of “Steve and Lin,” our wonderful next-door neighbors on the Cove handed me two brand new paperback books tidily bound by twine and ribbon. “I thought you’d appreciate these books,” she said. “He’s such a great writer, and they’re about India. I know you’ve been there and can relate to the settings.”

The author was Rohinton Mistry, about whom I knew nothing. In my literary ignorance, I’d never heard of him. Now that I’ve read his monumental novel, A Fine Balance, and have dived into Swimming Lessons, his collection of short stories, I can say I know quite a lot about him and his writing. Born into a Parsi[1] family in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1952, he studied math and economics at St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai. After emigrating to Canada in 1975 with his then fiancée, he worked for a time at a bank, of all places, before regaining his bearings and returning to school, where he obtained a degree in English and Philosophy from the University of Toronto. He then embarked on an ambitious and prolific writing career.

In my unlearned estimation (I am the quintessentially non-English major), A Fine Balance is a brilliant literary work. It’s an epic story of four primary characters[2] interwoven with an array of fascinating and well-developed supporting actors living, struggling in hope, despair, kindness, and cruelty, much of it inside the underside of India as it was in 1974. But mostly the story is a deep inquiry into universal elements of the human condition.

How would I the non-literary student know the book is a brilliant work of literature? Well, partly because I devoured and digested every single page of the 601-page work. If I were to depict the quality of the book, I would do so with a simple Venn Diagram consisting of three circles. Taken individually and together, these circles capture the essence that makes reading this 601-page book well worth the effort.

In the first circle resides imagery. Like small dishes of irresistible artisanal chocolates placed ubiquitously throughout an opulent mansion, Mistry’s use of metaphors and similes is nothing short of genius. His imagery is never forced upon the reader and never accompanied by the blast of a herald’s horn. With the dexterity of a great painter he works images in subtly, smoothly, naturally. My effort at such a craft would appear as cheap bright ink from a bargain-priced fountain pen. From Mistry’s imagination, the images flow like melted butter with honey on oven-fresh bread.

One of a hundred examples of Mistry’s virtuosity appears in the context of “the two tailors,” Ishvar and his 17-year-old nephew Omprakash (“Om”), running to catch a train. They are of the untouchable caste, the Chamaar (leatherworkers), of their village, but Ishvar and his brother Narayan (Om’s father) surprised everyone by training to become more respectable and prosperous tailors. Through one of a thousand subplots and caste violence, cruelty and injustice, they become poor again but not as poor as many: in the scene at hand, Ishvar and Om could afford to buy train tickets, saving them the trouble of having to jump the fence and hopping the train illicitly. The reader is transported to the grounds just outside the train station:

The end of the platform sloped downwards to become one with the gravel hugging the tracks. Here was the crucial opening in the endless cast-iron fence, where one of its spear-pointed bars had corroded at the hands of the elements and broken away with a little help from human hands.

The swelling knot of men and women trickled through the gap, far from the exit where the ticket-collector stood. Others, with an agility prompted by their ticketless state, ran farther down the tracks, over cinders and gravel sharp against bare soles and ill-shod feet. They ran between the rails, stretching their strides from worn wooden sleeper to sleeper [ties], vaulting over the fence at a safe distance from the station.

Though he had a ticket, Om yearned to follow them in the heroic dash for freedom. He felt he too could soar if he [were] alone. Then he glanced sideways at his uncle who was more-than-uncle, whom he could never abandon. The spears of the fence stood in the dusk like the rusting weapons of a phantom army. The ticketless men seemed ancient, breaching the enemy’s ranks, soaring over the barbs as if they would never come down to earth.

In the second circle of the Venn Diagram lies Mistry’s mastery of detail and brilliance as a narrator, as a story-teller. An example is his description of an enormous propaganda poster that appeared suddenly, towering over the slum, during the “Emergency” declared by the authoritarian Indira Gandhi.

The advertisements had been replaced by the Prime Minister’s picture proclaiming: “Iron Will! Hard Work! These will sustain us!” It was a quintessential specimen of the face that was proliferating on posters throughout the city. Her cheeks were executed in the lurid pink of cinema billboards. Other aspects of the portrait had suffered greater infelicities. Her eyes evoked the discomfort of a violent itch somewhere upon the ministerial corpus, begging to be scratched. The artist’s ambition of a benignant smile had also gone awry—a cross between a sneer and the vinegary sternness of a drillmistress had crept across the mouth. And that familiar swatch of white hair over her forehead, imposing amid the black, had plopped across the scalp like the strategic droppings of a very large bird.

Mistry’s command of descriptions and narrative cadence reminds me of master painters of portraits and intricate cityscapes; of great film directors whose genius for detail dovetails perfectly with a gripping story. Remarkably, plot and subplot momentum in A Fine Balance is sustained, not slowed, by detailed descriptions.

As impressive as Mistry’s literary skill is the sheer work ethic required to produce such a novel as this.

The third circle of the Venn Diagram captures the author’s deep dive into the bottomless sea of the human condition. He turns over every stone imaginable in his mission to explore motives, incentives, objectives, reactions to life’s vagaries. Much of it, sad to say, lands in a swamp of despair. If I could level a criticism of the book, it would be that in the case of nearly every character, “things end badly,” as the author himself puts it. Without hope at its end, you might say “the book ends badly.”

Perhaps, however, the reader’s expectation—or need—for hope misses the point of the book. Its message isn’t that we shouldn’t embrace hope or that we “should” do or not do anything in response to the characters and their respective fates. The book simply captures and illustrates the fine balance between hope and despair. It presents life as it is, not as we’d like it to be, and it is up to us to accept and adapt or succumb.

However another reader might react to A Fine Balance, I can say unequivocally that I’m not the same person now that I was before I read this remarkable book.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] The Parsis (meaning “Persians”) or Zoroastrians, were driven out of Persia by the Arab conquest and Muslim persecution of Zoroastrians in the seventh century. They eventually settled around what is now Mumbai.

[2]Dina, a middle-age widow from a family of means, but now somewhat estranged and living constantly in fear of being evicted from her apartment; Ishvar and his 17-year-old nephew, Omprakash (“Om”), tailors originally from a provincial village, who find their way to the “city by the sea” (presumably Mumbai, but never identified by name) in search of work and are hired by Dina to sew dresses she has under contract with an export company; and Maneck, the 18-year-old son of Dina’s childhood friend from the “mountains” (again, never identified by name, but unmistakably Kashmir), who rents a room from Dina while attending a technical college in the “city by the sea.”