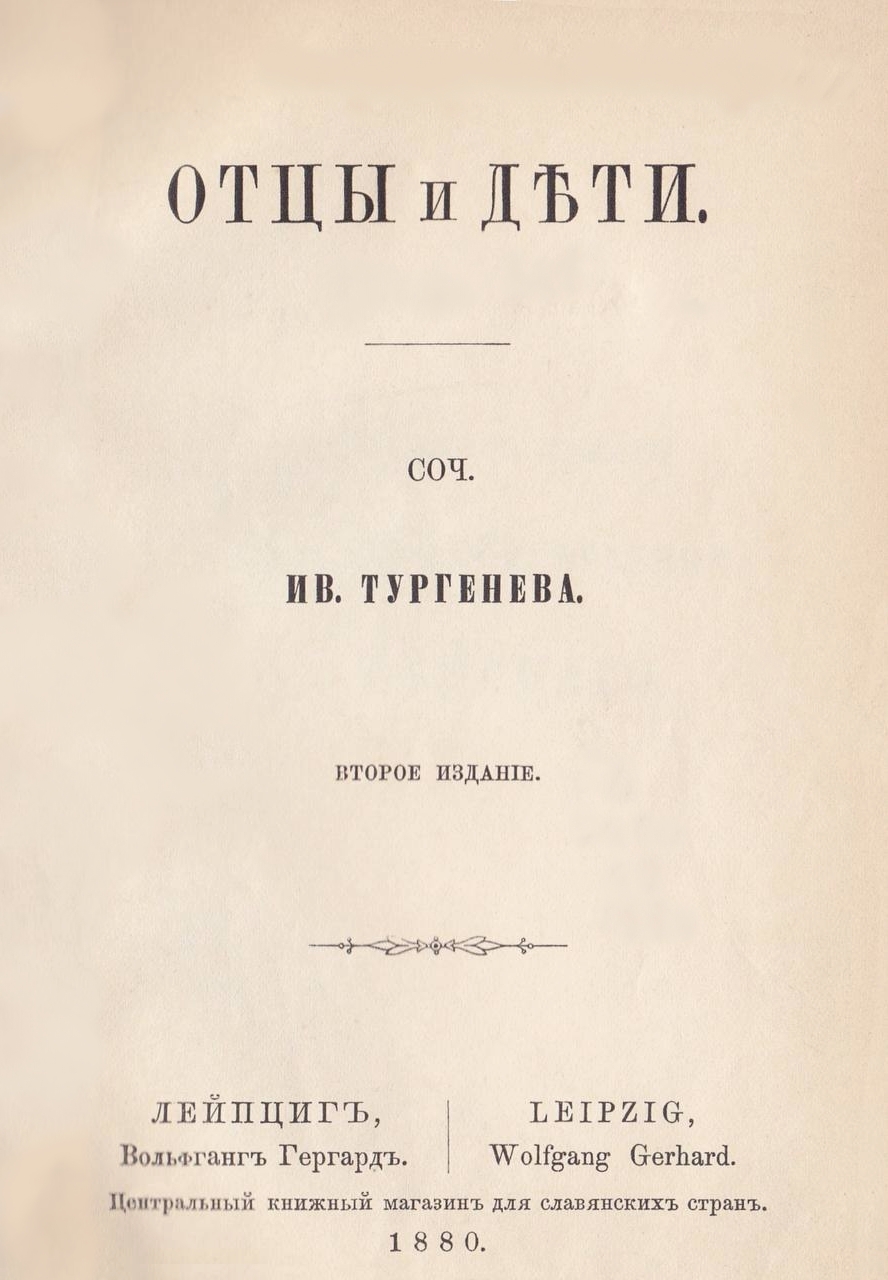

APRIL 4, 2025 – One morning earlier this week I finished reading Ivan Turgenev’s masterpiece, Fathers and Sons. It was a “slow race” to the finish, meaning I couldn’t resist pressing forward at the same time I wanted to hold back to savor every morsel. A few minutes before the end, I’d told my wife that I’d be all set to run errands with her (including a stop at Half Price Books and another at the post office to send book order fulfillments on their way)). She said “Fine,” and true to my word, upon reaching the last word of the novel, I gently closed it, took a deep breath and called out, “Okay.”

“Okay” is short for “όλος καλώς”—Greek, meaning, “all’s good”—but it fell short as an expression of my emotional and cognitive state just then. I waited until my wife’s book boxes were loaded into the car and we were backing out of the garage before I revealed aloud the true effect of Turgenev’s mid-19th century novel. “That book took my breath away,” I said.

It truly had—especially the last three or four pages—in ways I’m still processing.

The book reminded me of a gallery of paintings, a cycle of scenes that repeats from room to room but with slight variation—the countryside with a lonely dusty road cutting through; one of the three country manor homes featured in the book; a small pleasant garden outside one; the drawing room of another; a kitchen here; a pantry there; bedrooms down a hallway; a servant or two on the inside or loitering behind a shed and out of the master’s sight. Each scene is occupied by one or more of the main characters, each of whom is complicated, as all of us are except when we don the attire of simplicity—wittingly or not.

Fathers and Sons emphasizes character psychology over plot and was hailed by admirers (Flaubert; Manpassant; Henry James). Contemporary critics were many, however, and included “old [Russian] liberals” of the 1830s and 1840s, trying to keep up with Western mores, the new radicals who opposed them, and the Slavophiles, who eschewed the West and looked to Russia’s mystical religious traditions marked the correct path to Russia’s future. Turgenev’s pen and ink spared no one—not the gentry captive to their station and not the young Nihilist student doctor Bazarov or his admiring friend Arkady Nicoleivich Kirsanov; not the young widow of independent means and mind, Anna Sergeevna Odintsova, or her sister Katya Sergeevna, who winds up marrying Arkady; not even the recently emancipated serfs reach the end of the book without their flaws revealed.

Nor does the reader escape unscathed—drawn into the psychologically fraught exchanges between friends; between hosts and guests; between fathers and sons. One of the most intense is the rising conflict at Marino (the estate of Arkady’s father, Nikolai Petrovich Kirsanov, which he shares with his brother Pavel, and where Arkady and Bazarov are visiting) between the aging Pavel and the young candid man who recognizes no authority. The old man grows to detest the self-assured visitor and his offensively radical ideas. The tension culminates when the uncle with no purpose but to emulate English habits challenges the young man of objective science to a duel. The latter obliges, despite recognizing full well its absurdity. (No spoil alert here—both survive, though Pavel emerges from the foolish encounter with a flesh wound that grounds him for a few days—and that Bazarov, unharmed, expertly bandages.)

While Turgenev demonstrates mastery in molding his characters and directing their interactions, he performs as a virtuoso in the art of description—of things tangible and matters intangible. Bazarov’s untimely death in the home of his loving despairing parents who have little understanding of him; his farewell exchange with Anna Odintsova; his parents’ pathos in visiting the unkempt churchyard where he is buried, are nothing short of operatic in staging, libretto and echoes of the saddest music that tragedy inspires.

As I savored this work and pondered its timeless insights into the human heart, mind and soul, I imagined the book as both a collection of original portraits, still lifes and landscapes in concert with a fine musical work performed by an octet of winds and strings. I imagined myself as a visitor at a combination gallery/recital hall, equipped with little more than access to the descriptive plaques beside each painting and program notes to the music. Though impoverished in ability to paint or perform, I was vastly enriched by the exposure to Turgenev’s genius. I could readily appreciate how artists and musicians—and writers—would interpret this novel and extract from it an understanding of the human condition far deeper than my limited literature literacy or musical experience can reach. But again, in my case, anyway, to be exposed is to be edified.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

1 Comment

Wow. Wonderful description of what this book meant to you. Those Russian names…