JUNE 17, 2023 – (Cont.) If I could laugh at Mother wearing a crash helmet at the cabin, I was wholly annoyed when trying to read in the living room up there with Mother. I don’t think I ever cleared a page without her making a random comment or asking a question about one thing or another. If it annoyed me, it drove Elsa to distraction. I remember once when Elsa, wanting to concentrate on reading a novel, just got up out of her chair, stomped off to the front porch, and used the French doors between the living room and the porch to communicate her disdain for Mother’s constant interruptions. It was shortly after that, actually, when I happened to be driving Mother up to the cabin. She couldn’t stop talking. I remember timing the space between her random comments and questions, as if I were counting the lapse between a flash of lightning and a clap of thunder. ‘One-thousand one, one-thousand two, one-thousand three, one-thou . . .’

“Did you hear about . . .” For nearly three hours, I never moved past ‘one-thousand five.’ I wanted to scream, as I remembered Elsa getting out of her chair and storming off to the porch.

But that was nothing compared to Mother at the movies. In the first place, when I was nine or ten, it bugged me to no end that she insisted on calling them “pictures,” though I learned to tolerate “pictures” after she explained that that’s what movies were called when she had been my age. What drove me crazy was all the noise Mother made during a movie or a “picture” or whatever she wanted to call them in front of me (not my friends). Fortunately, Mother didn’t attend that many movies with my sisters and me, but when she did, hardly fifteen seconds passed before Mother would let out a grunt or chuckle of some sort. It embarrassed me to the point where I would glare at her with exaggerated disapproval, which in my little mind proved to the people behind us that I didn’t know this woman, and in the theatre lobby after the movie, I would do all I could to distance myself from Mother.

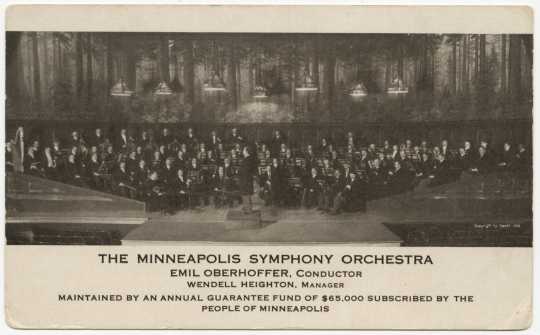

However, after Elsa and I took our disdain to an extreme, I don’t think I ever again wholly, openly disowned Mother in public. The occasion was a community concert at the Anoka High School when I was about 12. Every so often, members of the Minneapolis Symphony (now the “Minnesota Orchestra”) would come to town, and since my parents couldn’t get enough music down at the Symphony’s home at Northrup Auditorium on the U of M campus, they would take us to the “community concert” series as well. On that particular night, it was just Mother, Elsa and I. Throughout the concert, Mother had to “hmm” and otherwise audibly express her approval of the music. What put Elsa and me over the top, though, was Mother’s vigorous applause. While normal people clapped normally, Mother had to slap her hands hard and in double-time—for about five seconds, when her tic would abruptly interrupt her rapid clapping. But a second later, after her jaw had closed and her head had snapped back from its little side-trek to the left, her hands resumed their frenetic movements. I remember Elsa sitting on Mother’s right and I to her left, simultaneously peering at Mother with the same disdainful look. At intermission, we bolted from Mother as fast as we could, an act of disavowal that we repeated after the concert.

As she was wont to do, Mother found any number of acquaintances to chatter with after the concert, allowing Elsa and me to move well enough away until everyone had cleared out and we could accompany Mother—pretty much unnoticed—to the car for the ride home. Somehow, however, we lost track of Mother altogether, and eventually Elsa decided that we should simply hike home in the dark by ourselves. It was about a mile and a half, which gave us plenty of time to share each other’s vitriol over Mother’s ridiculous public behavior.

I fully expected Mother to have figured out that we had walked home and that we would see the Buick Super in the driveway when we ourselves arrived. But the Buick wasn’t there. We let ourselves in. I don’t know about Elsa, but I began to worry on my own. Where was Mother? I felt a twinge of guilt over our public disdain—after all, Elsa and I had hoped that people would notice it—and now felt anxious about Mother’s whereabouts. Was she okay? The minutes turned into a half hour. Still no Mother. What if something awful had happened? What if she had gotten into a really bad car accident? What if she had taken offense over our rejection of her, and what if she had decided to reject us and had decided simply to drive off in the Buick to parts unknown, never to be seen again—never to have to embarrass us again? I began to feel terribly unsettled. The phone rang. Elsa answered it. It was Mother, calling from the home of a friend whom she had met at the concert and had invited her to stop by on the way home. After a curt exchange, Elsa handed the receiver over to me. “Mother!” I said. “Where have you been?” A feeling of great relief poured over me at the same time anger over a sense of abandonment mixed with heightened guilt over our having abandoned her.

“Where have you been?” she asked. There was no anger, no anxiety in her voice, but her tone of wholly uncharacteristic sarcasm hit me square in the heart. A few other words and we were off the phone. Five or ten minutes later, the Buick pulled into the driveway. There would be many times later when I would be embarrassed by Mother and many times later when I would rudely reject her, but never would I do so quite so openly as I had that night at the concert.

I don’t know how I would have reacted when, as Jenny told me years later, Mother had stood up and made an open statement at a crowded forum following a production of the Minneapolis Children’s Theater. “Another question,” the theater director said from the stage, looking out over the sea of parents and their children.

Mother raised her hand, and when the director pointed at her, Mother stood, as people looked her way attentively. “I just want to thank you,” she said, “for giving expression to the human spirit.” Jenny was quite young on that occasion, but when she recounted the story, she told me how impressed she had been at the time; how moved that our Mother could say such a thing in public; how our Mother, whom we knew as the “math mom,” could have such a deep and expressive heart. Jenny’s reaction struck me deeply, for in revealing Mother’s true nature, it also tore at my heart, for I recognized that Mother’s zaniness had all too often blinded me to her dearest and most abiding attributes.

Yet none of Mother’s efforts and activities, mental, organizational or otherwise, surpassed her involvement with faith and church and all that they entailed, symbolized, and manifested.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson