MAY 13, 2025 – A few days ago I finally finished reading The Crimean War by the British historian, Orlando Figes. I’d mentioned this book several months ago on this blog and remarked that prior to “going back to college” to study Russian history, I was as ignorant as the next American about the Crimean War. Now that I’ve digested the 492-page book about (a) the circumstances leading up to the conflict, (b) execution of the war, and (c) consequences, direct and indirect, I feel as if I have a much better understanding of the how and why of subsequent developments in Russian, European, and Middle East history. Such is the effect of studying history.

Apart from the deeply fascinating analysis of the geo-political and religious tensions that gave rise to the Crimean War and how the conflict resolved—or exacerbated these antagonisms—Figes devotes a fair amount attention to the war itself, the centerpiece of which was the 11-and-a-half-month-siege of Sevastopol by French and British forces.

I’ve read about a lot of wars, big and small, and I have yet to learn about a war that wasn’t just plain stupid; even WW II, which is often described as the last “good war” that Americans have fought. No. I say, that war was just as insane as the rest of them. What I find absolutely abhorrent, not to mention embarrassing, is how members of our species can unleash such cruel and destructive physical force and violence against fellow humans. This perspective hasn’t yet converted me to “turn-the-other-check” pacifism any more than police brutality has pushed me to call for defunding the police. Once the bad guys are unleashed and dead-set on burning down your village—while everyone near and dear to you is at home—what choice do you really have but to do all you can to resist?

Nevertheless, as wars go, the Crimean War was especially stupid; stupid in how it turned into a war in the first place, and even stupider in how it was conducted. But this assessment is that of a 21st century armchair student of history with knowledge of but no real appreciation for the divide between the Eastern Church and the Western Church; why Great Britain feared the “Russian menace,” particularly the implications for the Empire’s colonial crown jewel—India; the weaknesses of the Ottoman Empire (“the sick man of Europe,” as Tsar Nicholas I labeled it); the pan-Slav movement in the Balkans; Napoleon III’s need to restore the prestige of France (and solidify his own); the messianic designs of the Tsar as protector of the Orthodox Church . . . and so on . . . each a contributing factor to the Crimean War, fought from October 1853 to February 1855, at a horrific cost in human lives and suffering (at least 750,000 soldiers and sailors died in battle or from disease; total civilian casualties were widespread but never calculated). It was the last war in which tactics of the Napoleonic Wars were deployed (e.g. the Charge of the Light Brigade), along with chivalry (e.g. “timeouts” during the heat of battle so that each side could claim its dead and wounded).

Yet, the Crimean War was also the first conflict involving total war against civilians as well as between militaries; the first in which trench warfare (along 120 kilometers’ worth around Sevastopol), steamships, railways and telegraphs, and rapid shooting, long-range, highly accurate rifles (the French Minié rifle) played key tactical roles. For anyone keeping score, in the siege of Sevastopol, 150 million gunshots were fired and five million bombs and shells were exchanged between the besieged Russians and the besieging French and British.

Though the Allies prevailed, little was gained strategically from the fall of Sevastopol. It had been largely obliterated. What few objects weren’t crushed to dust were looted by the vistors.

However “stupid” the Crimean War, it produced profound outcomes for the world.

The war exposed Russia’s backwardness vis-à-vis the Western powers and hastened the end of serfdom. Though the Allies “won,” in the end, it was at the cost of a deep-seated Russian resentment toward the West. The war destabilized the Balkans, planting the seeds for WW I and led to an expanding role for Great Britain in the Middle East. Furthermore, the long-standing alliance between Russia and Austria, which was never an actual belligerent, was up-ended by the war, paving the way for the emergence of Germany, as a nation state, Romania, and unification of Italy.

Wars almost never turn out strategically as any belligerent expects or desires. Likewise, tactically few battles go according to plan. And just when cholera was reaping mercilessly soldiers bound for the frontlines, frostbite and horrific living conditions competed with enemy shellfire for striking down soldiers who escaped the cholera.

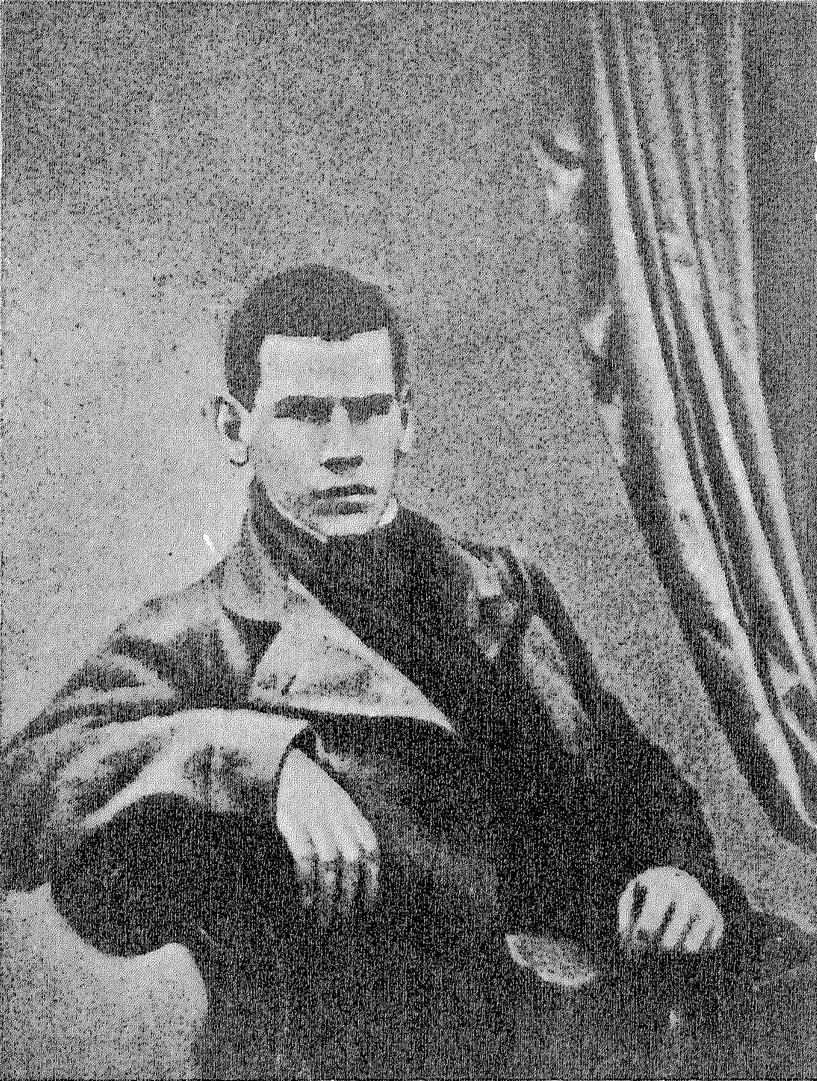

The Crimean War was the first in which photographers and journalists were on hand to “de-glorify” armed conflict[1]. One reporter who launched his writing career was a young aristocrat, an army officer named Leo Tolstoy. Initially quite enthusiastic about going to war and finding the center of action, he came to see—and report—on the ugly side of reality. His experiences informed his most famous work, War and Peace.[2] Thus, perhaps it can be said that one of the stupidest wars in European history at least produced one of the best pieces of world literature—and one that Professor Stavrou argues is worthy of being read not simply once in the lifetime of every discerning reader but once every year of a lifetime[3]. Though I’ve read it twice (over my lifetime to date, it’s back on my reading list—along with Tolstoy’s first collection of published stories, Sevastopol Sketches).

Back to The Crimean War—the book—it too is worthy of a second read, along with a companion historical atlas. Though the book does include some excellent maps, putting it ahead of most histories, which are glaringly deficient in that regard, the reader would benefit greatly from a large atlas lying within reach; especially the reader without a detailed knowledge of the Black Sea shoreline, the physical geography of the region, and historical boundaries of various nations, empires, peoples of the eastern Balkans, the Caucasus and the Ottoman Empire. (Sorry, but Google Maps on your iPhone isn’t up to the task.) Figes leaves few stones unturned, and as with his other works, his writing is eminently accessible and replete with “attention Velcro.” Despite the tome’s length, there was nothing that struck me as superfluous. A solid piece of scholarship very well presented, the book reminds the reader how much more there is to learn about the world—and how gratifying it is to learn.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] This reportage would have a profound effect in turning public opinion against the war, but as would be the case all the way to the present—exposing the harsh realities of war doesn’t seem to turn that opinion against war generally.

[2] Originally, the novel was called The Decembrist and featured a member of the Decembrists (revolutionaries who sought major reform at the outset of the reign of Nicholas I in 1825), who in the 1850s returns from a 30-year exile in Siberia and discovers an intellectual movement set on reforms at the start of Alexander II’s reign (1855). The deeper he waded into things, however, the more Tolstoy realized that the Decembrists’ movement was rooted more in Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Russian than in the Crimean War.

[3] Professor Stavrou, however, tries to read “a novel a week,” and gets by just fine on three hours of sleep every night plus a catnap in the afternoon. In other words, he has far more reading time capacity than most of us do.