FEBRUARY 17, 2025 – (Cont.) The first letter was from my dad, who died 15 years ago this coming May. As I unfolded the single sheet of lined paper and exposed his familiar handwriting to the present light, the slight disturbance of air sent the time machine “datometer” into a dizzying blur. Dad’s distinctive cursive, so even and legible, disciplined and elegant, no matter what the context—a heartfelt letter or a list for a trip to the hardware store—brought him back to life with the same realism as would a high resolution recording of his voice or video of his image. My mere grasp of the page powered the time machine and directed it straight away to the cabin and into the woods of Björnholm, then high above the trees and with another woosh, out over the lake where the machine then plunged to the surface. My stomach took a full second to catch up.

The contraption hovered 100 feet from shore, as the whirling datometer slowed, then stopped at “July 1998.” By means known only to invisible forces, the bulky time machine transformed itself into our old Alumacraft rowboat with Dad at the oars, pulling straight and true. Together we surveyed the legions of trees that he so admired and for which he cared so much, the Creator having appointed him as their protector and champion.

“Look at that white pine just to the left of the tallest Norway behind the oaks,” he said. “It’s now spreading its boughs over the maples back there.”

“Just plain regal,” I said.

“Magnificent. I remember when that was a sapling no more than 10 feet high . . . you know, for years it was crowded out, but give the white pine time and they’ll needle their way through, just as that tree has, always reaching for the sun. The persistence of the white pine, especially, is irresistible.” It was just one of hundreds, thousands of trees along the shore, but in Dad’s view, they were individual trees, like people, each with its unique personality and characteristics.

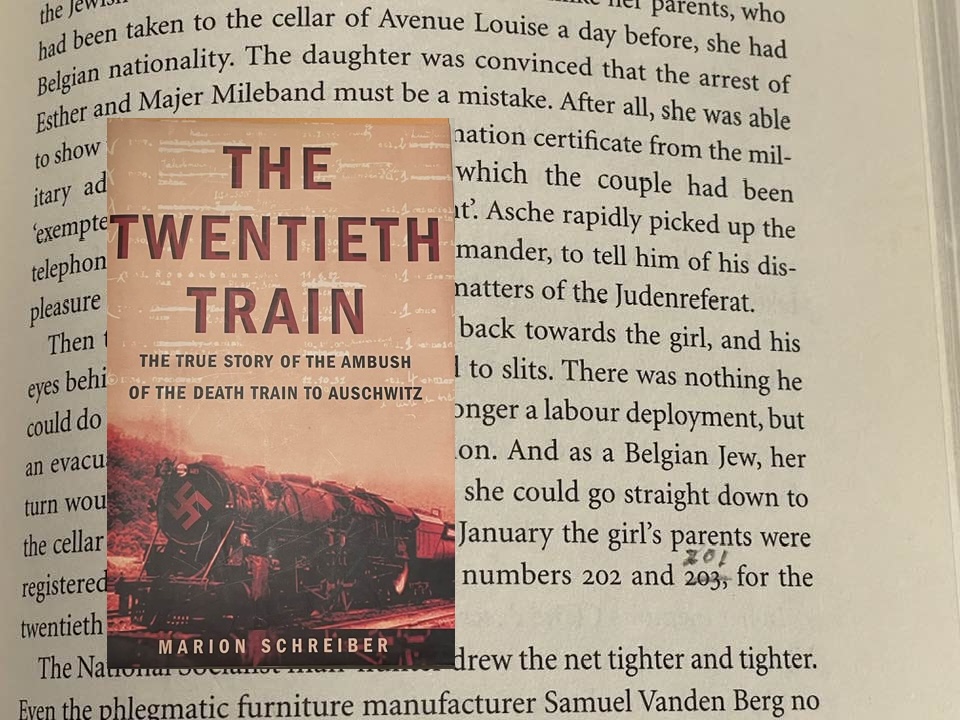

Without warning the time machine zoomed to the den of my parents’ home in Anoka as the datometer whirled to May 11, 2008. With unbridled enthusiasm Dad told me all about his latest reading adventure: The Twentieth Train: The Trust Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz by Marion Schreiber, a book about the expulsion of Jews from wartime Belgium—a book he then handed off to me with his standard recommendation, “You’ve got to read this.” [1]

With the same focus he applied to every endeavor, Dad was a meticulous reader and possessed a lockbox for a memory. The books that he’d read, then given to me invariably included typos and other errors encircled. On page 119 of The Twentieth Train, the author cited the prisoner numbers—“202” and “203”—assigned to Ester and Maijer Mileband, just two of innumerable characters, each like a tree in Dad’s woods[2]. With a pencil he’d stricken “203” and written in, “201.” Curious, I searched high and low for the basis of the correction. I found it buried in the 40-page appendix, which in fine print listed all 1,619 Jewish prisoners transported by train from Belgium to the death camps. The characters “Mileband, Maijer Brajs” and “Mileband-Rottesman, Ester” were listed as prisoner numbers “201 and 202.” As a perfectionist down to the minutest detail, Dad had no equal.

The datometer again whirled out of control as I flew at the speed of synapses from my earliest memories of Dad to his funeral and the burial of his ashes. When my eyes settled back on the date of the letter, the spinning reversed, then stopped at “February 19, 1981”—the day after I’d departed Minnesota for California.

“Dear Eric,” I read—just as Dad entered the room and took a seat across from me, his deep blue eyes lighting up his countenance. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] “May 11, 2008” was lifted straight from the last page of the book where, as was his custom, Dad had penciled in the date on which he’d finished reading the work.

[2] The Foreword to the book is introduced by the anonymous quotation, “Anyone who saves one human life, saves an entire people.” Dad certainly subscribed to that maxim—whether applied to trees or people.