MAY 18, 2025 – We’ve all been long exposed to the adage that “history repeats itself,” as more recently amended to, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” Weary of this cliché, I find more useful the insights that an examination of history, similarly to close analysis of literature, reveals about the psychological make-up of leaders and followers. An intimate understanding of how we think and feel is critical to a grasp of the behaviors of people who ascend to power and equally important, the mindset of people who allow or enable the power-mongers . . . to “monger.”

For years now, more than a cottage industry—more aptly called an industrial-gauge industry—has mushroomed over the most overtly bizarre American political figure of our age and certainly the most over-exposed character of our times thanks to the media that have accompanied and largely created that man. Legions of observers are members of this industry: professional pundits; outcasts from the president’s inner business and political circles; estranged family members; political opponents; political scientists; scandalized citizens. Each of these critics has advanced various refinements of the same basic assessments of both the man and his movement.

Metaphorically, the guy is a hot-butterscotch sundae—all fat and sugar; no nutritional value—and atop the whipped cream crowning the soft-serve ice cream is a red-dyed grape masquerading as a cherry. The grape, in turn, symbolizes what the best of cartoonists couldn’t match: the man’s parody of himself.

If the “butterscotch sundae” is the centerpiece of today’s political table, it’s not alone. Surrounding it and indeed, maintaining its viability despite rising temperatures, is a large supply of crushed ice of various flavors. The ice is divided among a multitude of bright red paper cones, each bearing the acronym “MAGA!” in contrasting white.

How in the world, we critics ask—and keep asking—did this freak show come to pass?

A long litany of causes has been assembled and endlessly analyzed, tweaked and critiqued. Everyone has a favorite theory, from Biden’s alleged dementia to the failure of the Progressive Agenda to the failure of communicating effectively the Progressive Agenda, to the lack of a plan, to the lack of a spine.

An offshoot of the central focus of “Why?” are the flashing warning signs, from Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century to Blowback by Miles Taylor to Peril by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa to what our own lying eyes and ears are exposed to in the daily reports of grift, corruption, incompetence, gross ignorance, chaotic economic policies, conflicts of interest, nods to tyrants, disregard for the rule of law, and cruel treatment of human beings.

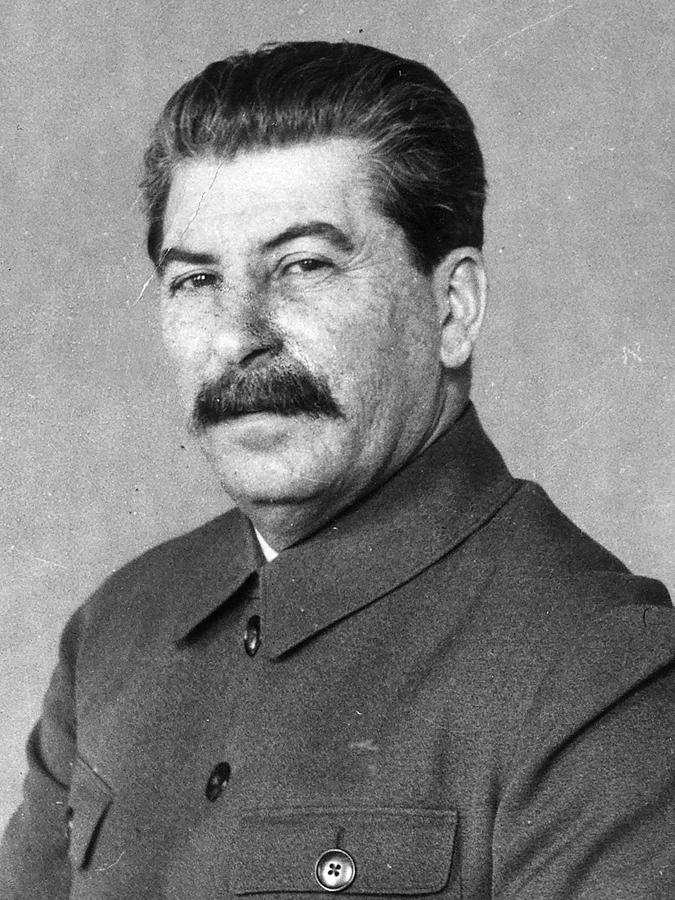

Today while reading The Great Terror: A Reassessment by Robert Conquest, I discovered one of the best analyses I’ve seen of Stalin’s purges. Along with most Western students exposed to that disturbing phase of Soviet history, I’d always wondered, how could so many people “go along” with the unfathomable terror—in its scope and scale? Most puzzling: why did so many Communist Party members go along with the outrage? How could so many of the victims, even, walk all over their own tongues to confess? Were they driven by fear and torture or were other factors at work? In Conquest’s definitive work on the subject, I discovered some revelatory insights—not only into what transpired in a far off land in a relatively far off time but into what’s happening in our own place in the current era.

We can hope that American autocracy will never reach the record of Stalinist Russia, in which show trials based on confessions under duress and evidence fabricated from whole cloth were followed by pre-cast sentences of execution. The total number of casualties by exile or execution—or first by exile, then execution—is difficult to ascertain, but at a minimum, the commonly held view is that 18 million prisoners passed through the gulag and 1.5 million to 1.7 million of those prisoners died in the camps. Excluding the exiled, 800,000 people were executed. (These figures don’t include the estimated millions who died of orchestrated starvation in the Holodomor in Ukraine (1932-33).) At the vanguard of these staggering statistics were the “Old Bolsheviks”—the original revolutionaries who were close comrades of Lenin and Trotsky at the outset of the October 1917 Russian Revolution, the Civil War that followed and the first couple of years of consolidating power. To tighten his unassailable grip on absolute power, Stalin eliminated all opposition, whether it was real, potential or imagined on the basis of paranoia.

The Stalinist epoch reveals many of the same human behaviors that drive MAGA and the Republican Party’s universal embrace of its current leader. These traits were not unique to the Soviet Union nor are they the sole drivers of the MAGA agenda in the U.S. today. But three characteristics appear to be universal across time and place.

First is the merciless smearing of one’s opponents. This occurred relentlessly in Stalin’s Soviet Union. Initially, it was the “rightists,” then the “leftists,” then the “Trotskyites,” then the “Zinovievites” and the “United Opposition”; followers of Kamanev; the “Central Group” and members of the plot to assassinate “our beloved Kirov,” who, of course, was murdered by the direct command of Stalin himself. From the perspective of most Soviet citizens and a good many Westerners, liquidation of “oppositionists” was justified, given the ubiquity and seriousness of the threat they allegedly posed not only to Stalin but to party and country.

Time and evidence revealed during Gorbachev’s glasnost expose the falsity of Stalin’s smear campaign. But we can also see its effectiveness. Now turn to the mantra-like bombast of other smear campaigns, not the least of which is the harsh and sweeping portrayal of jurists, science experts, journalists, undocumented immigrants, popular entertainers, and members of the Democratic Party as “extreme radical leftists.” Call anything something it isn’t, and after sufficient repetition, the “something” is viewed as whatever you choose to call it.

Second, and tied to the first tactic above, is “off-loading” mistakes, problems, accountability to innocent parties. In Stalin’s time, this was an effective method of diverting the public’s perceptions from reality. “If only Comrade Stalin knew,” the unknowing people would say, “he would do something to set things straight; if only he knew how bad we have it because of [counter-revolutionaries, plotters, schemers, would-be assassins, miscreants and criminals], he would have them all shot . . . for our sake and the sake of the country.” Not all the hard-working, suffering people who said this were dumb, lazy and mean, but they were easily convinced to loathe and fear conspiring scapegoats.

We see the same device deployed today: blaming plane crashes and other malfunctions on proponents of DEI; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine . . . on Ukraine; the high cost of living on “waste, fraud and abuse” among federal workers; crime on undocumented migrants; threats to Republican majorities on voter fraud; economic. Once these connections are established by the drumbeat of baseless assertion, breaking them becomes all but impossible.

But it is a third feature of the Stalinist era that explains in large part Republican surrender to the whims, edicts and misguided notions of the party’s leader. From a modern perspective, we find preposterous the slavish obedience of Communist Party members during the tyrant’s reign. Fear, obviously, was a constant factor, but as Robert Conquest emphasizes in The Great Terror, the party faithful believed—many quite sincerely—that if they “rode out the storm”; if they held tight to their positions and party membership, then when Stalin died or was deposed, they would be in place to take over, to lead the party to the next level. This rationale or rationalization created a raft of moral dilemmas, of course, but when it comes to the lust for power, survival is a threshold prerequisite for achieving, then holding, and eventually expanding power. In light of these dynamics, the expection of “spine,” let alone integrity, among Republicans is unrealistic.

We are too far down the path of disruptive autocracy to repair our fractured democracy anytime soon. What took a mere 100 days to blow up much of our nation’s institutional bedrock will take at least a generation to restore. Perhaps some of it will never recover. The human capital that Russia lost in the Purges was incalculable. Similarly, what America has lost thus far will cost us dearly both in the short run as well as over the long haul. In any event we shouldn’t be surprised—nor necessarily discouraged. What’s playing out in front of us is a very old show in the familiar theater of the human condition.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

3 Comments

Great historical perspective. Trump is following a well worn playbook of all past tyrants.

Thank you for your insightful “Parallels “. I often forward your blog to my daughter, Lisa, as I did this one.

As an AP Euro history and AP World history teacher at MoundsView, she finds her students to be inquisitive and committed to learning. She enjoys the challenge of teaching those courses. I suggested to her that she might consider having you as a guest lecture. I wonder if you would entertain that idea. Connie

Connie, I’m flattered that you think I have the “chops” to be a “guest lecturer” in Lisa’s AP history courses. I’m impressed by her role–do her students begin to appreciate how lucky they are? I haven’t talked with her since she was quite young, but I know she went on to get a superb education, and knowing the stock she comes from, she’s a “smart cookie”–but teaching AP Euro and World history?! That’s fantastic!! I’d love to chat with her, at least, about (a) her take on the world; and (b) some thoughts I have about the study of history (I can get pretty fired up about it!). If I pass the “audition,” I’d be thrilled to share my enthusiasm with a class of fellow students of history (I’d start off by recounting Professor Stavrou’s “three levels of learning.”) Let’s talk. –Eric