MAY 10, 2025 – Today my wealth—and that of my friends Matt and Ravi—increased beyond measure. By “wealth” I don’t mean how that term is typically defined and perceived in our society. I mean the sum of one’s hope, faith, love, and friendships. This remarkable increase in wealth was bestowed upon us by a most extraordinary human being whom I introduced to my readers back in January, the inimitable Professor Theofanis G. Stavrou.

Last December, Matt, an indefatigable student in a range of disciplines, had registered for the professor’s spring semester survey course at the University of Minnesota, Russian History from Peter the Great to the Present. Matt encouraged me to register, and off we went . . . back to college. After the introductory lecture, I told Ravi—another insatiable learner—about it and urged him to join us. We would become known as “The Three Musketeers” among a class of nine undergraduates and several other more senior “auditors.”

As I reported in January, at 91 the good professor is as sharp as the key of C# Major (and A# minor) and exudes charisma—a perfectly Greek word befitting a Greek Cypriot[1]. Impressed by his first lecture, I sent him an email expressing my deep appreciation and providing a bit of background as to what had drawn me to the course. In the correspondence that ensued, I invited him to lunch at some point, over which the “Three Musketeers” could learn more about his interesting background as a scholar, as a person.

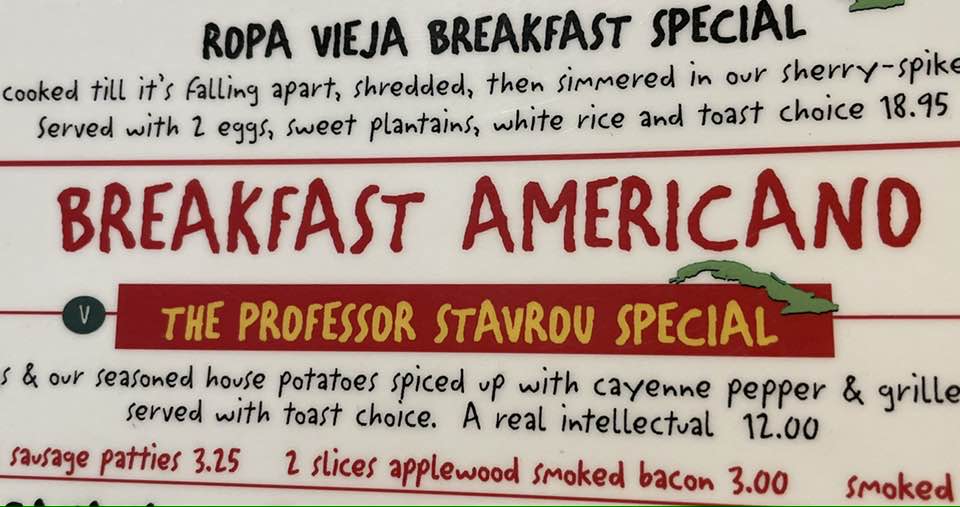

He took me right up on the invitation, but being the ever so gracious person that he is, Professor Stavrou insisted that he treat us . . . at his “favorite Cuban restaurant,” located in south Minneapolis. Little did we know . . .

The “favorite Cuban restaurant”—Victor’s 1959 Café—turned out to be a local institution with broad acclaim. Upon crossing the threshold, the first-time visitor steps into a world like none other in the Twin Cities. A veritable “hole in the wall,” the place is jam packed with patrons, and the cheerful servers move frenetically but gracefully between kitchen and booths/tables. Every flat surface, it seems, including the entire ceiling, is covered with finely scripted graffiti left by several generations of loyal patrons.

As we soon discovered—and kept discovering throughout the two-and-a-half hour-lunch and conversation extravaganza—the food was spectacularly delectable, and the Spanish wine and chocolate con leche were just as delightul. But then came the wonderful surprise: the restaurant has been long owned and managed by Niki, the Professor’s daughter! And as one of the servers rushed by—and later took our group shot of us—Professor Stavrou affectionately identified the man as his grandson—no, his great-grandson.

I can’t remember a time when I was made to feel so at home in a restaurant—and where the food, drink, ambience and above all, the conversation, were so delicious. Each of us “Musketeers” now realized that however much impressed we’d been by this master scholar in the classroom, this man Stavrou was an exemplary human being; a remarkable citizen of the world; a multi-faceted individual with an unmistakable—and unerring—genius for drawing out the best in people and thereby presenting the best in himself.[2]

As one can imagine about an extended, thoughtful, thought-provoking, wide-ranging, scintillating, entertaining, informative conversation with un professeur par excellence who is 91 years old and in full command of electrifying faculties (no pun intended), the participant is left to savor a long string of insights and amusing and amazing anecdotes. As a self-styled writer, I wanted to jot down notes for later reference, or as any self-respecting journalist would do, record the conversation end-to-end. Neither crutch, of course, was appropriate for the setting or our principal purpose: nurturing friendship while breaking bread together. In the middle of things, someone close to the family and the restaurant stopped by our booth to greet Professor Stavrou. When the latter started to introduce us, I said, “We’re his students,” whereupon our teacher corrected me: “No, friends.” Matt, Ravi and I could not have been more flattered.

In my journal, I’ll record more of the details of the sumptuous conversation, but here I must mention three especially noteworthy features.

The first involved Eugene McCarthy, the Minnesota poet-professor (at Macalester College in St. Paul) who was elected to the Senate and who ran as the anti-war candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. (May the record reflect that McCarthy’s remarkable performance in the New Hampshire primary led to LBJ’s dropping out of the race.) Fast forward a few years into the 1970s, and Professor Stavrou was preparing to lead a group of university students on a tour of Greece and Cyprus. Out of the blue he received a call from McCarthy, who’d somehow heard about the tour and asked if he could join it. Professor Stavrou thought it best if the former senator didn’t; that if he were with the group, his presence alone would be too distracting and would detract from the students’ experience. True to character, however, Stavrou told McCarthy politely that maybe sometime in the future, just the two of them could take the same “tour.”

Almost 20 years later, sure enough, the poet-professor-turned-politician called Professor Stavrou to take him up on his offer. True to his word, the latter agreed, and the two went forth. As the professor—Stavrou, that is—told us today, they had a wonderful time, and he, Professor Stavrou, learned more about American political science during their two-week sojourn in the eastern Mediterranean than could be studied in an entire university course.

The second special feature of today’s conversation concerned Professor Stavrou’s participation in the founding of the University of Cyprus in 1992. He’d been hand-picked in 1989 by the then president of the country to join a commission of several Greek Cypriot scholars among the diaspora. The group’s main condition (apart from adequate funding) was non-interference on the part of the government. The enlightened president of the University of Minnesota sanctioned Stavrou’s efforts, but Stavrou wasn’t about to short-change the people who counted most in his starlit career: his students. Accordingly, he commuted weekly between Minnesota and Cyprus for the work of the commission while maintaining his teaching commitment[3]. The enterprise was a spectacular success from its inception, and today the university boasts a student body of 10,000. Professor Stavrou has arranged for his personal 25,000-volume library to be donated to the university.

The third special story we heard reached back to Professor Stavrou’s home village in the north part of Cyprus, where there was a 50-50 mix of Greeks and Turks. In a wonderful example of the better angels of our nature, he described how grain harvesting was a home-based, community affair. After reaping, the stalks were placed on the floor for threshing the grain. Next came winnowing, accomplished by tossing the grain in the air (in a light breeze) to separate the (lighter) chaff from the (heavier) grain. Professor Stavrou then made the point that if neighbors happened to be passing by when a breeze was stirring, they would help seize the moment for the winnowing. It was a story of the village writ large; a reminder that “it takes a village” to raise us human beings and to sustain us—however rugged the individual’s exterior might seem.

Before we parted ways, Matt and our good friend compared notes about favorite Greek restaurants in the Twin Cities—for the purpose of our next rendezvous. Earlier in the conversation, Matt had set bells a-ringing when he revealed that his late father had been a long-time professor of economics at the University. Professor Stavrou’s face lit up when he made the connection and recalled the halcyon days when inter-departmental socializing was far more prevalent than it is today. This triggered other Stavrou connections familiar to Matt and some that snagged Ravi by way of his own professional interactions with friends and acquaintances of the professor. Even I could claim one by way of Professor Warren Ibele, a close friend of my parents, who was Dean of the Institute of Technology for many years—and as I posted earlier, was a visitor to the Soviet Union via a cultural exchange in the early 1960s. All the world’s a village.

When we stepped out into the sunshine, I felt awash in hope, faith, love, and friendships. Though the four of us are wholly unified in our disdain for what Musk and MAGA have done to this country, none of us touched on politics—beyond Professor Stavrou’s citing a recent paper by a University colleague about academic freedom. Our conversation was completely uplifting and encouraging. Here was a model citizen of the Republic as committed as ever to the ideals that make this country so unusually good—and a person whose life’s work has given those ideals very real practical effect. And there with the standout representative of the generation ahead of us were two grand people of my generation who have likewise contributed so much to rendering the world a better place. Two of the four of us had origins outside this country—a reminder of the genius of America as a place of “all-comers” (once we atone for suppression and eradication of the native population and servitude of people whose roots are African). To borrow (and improvise) from Senator Paul Wellstone, “We all become wealthier when we all become wealthier” . . . and when we understand the nature of true wealth.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] He came to America in the late 1950s and obtained his PhD from Indiana University. In 1960 he was hired by Professor Harold Deutsch, a leading historian of World War II, to join the history department at the University of Minnesota. Underscoring the astonishing math, that was 65 years ago.

[2] Elsewhere in the conversation we learned that Professor Stavrou had advised 56 PhD candidates at the University of Minnesota, many of whom went on to their own distinguished academic careers, hither and yon. One aspect of today’s conversation that developed into a theme, really, was Professor Stavrou’s dedication to his students and their welfare. Concomitantly, throughout his career he has eschewed the ivory tower attributes of academia and has worked hard to foster connections between the realm of scholarship and the realities of the surrounding community. Far from being inaccessibly “professorial,” our hero is a warm and compelling emissary of higher learning and “learning for the sheer joy of it,”