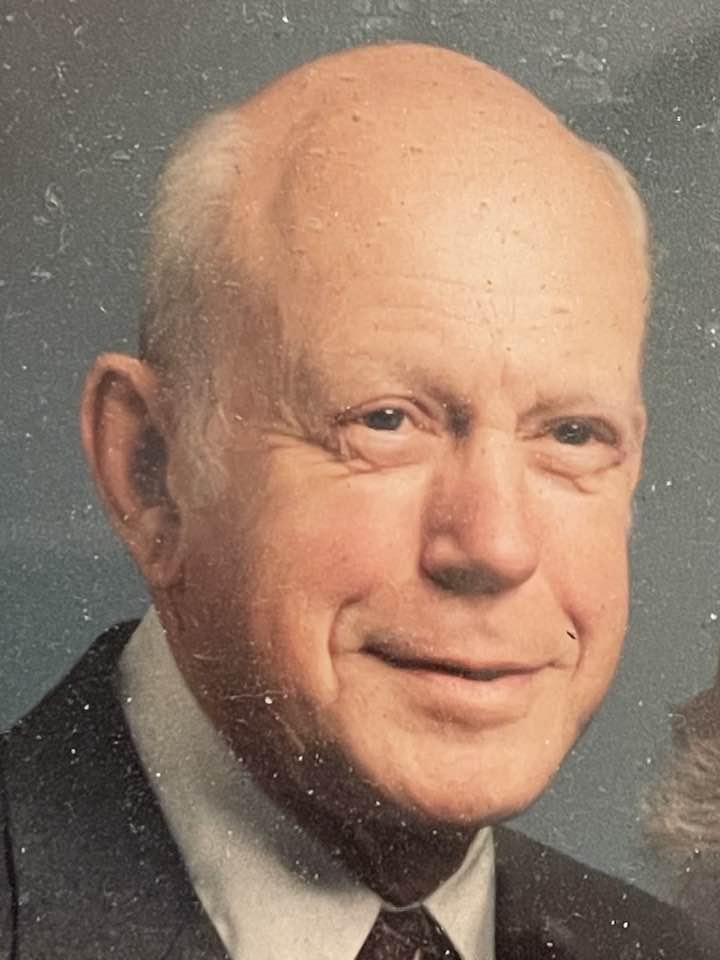

MAY 20, 2025 – Had our dear old dad lived to be even older than he was when the curtains closed at 10 days shy of 88 years; if he’d escaped the multiple myeloma that killed him and he’d dodged any number of other potentially terminal events, he would’ve turned 103 today. An early morning text from my oldest sister to my other two sisters and me reminded us of this milestone:

Thinking today of our handsome, dignified-yet-whimsical, nature-and music-loving father. More and more I’ve come to appreciate his remarkable qualities and his devotion to our family. How blessed we’ve all been!

A short time later, the next sister replied:

Nina, that is so well expressed! To be the children of a man who shared his love of life and who appreciated beauty and excellence the way Dad did, and then to absorb all our lives how deeply he loved and cared for us and our mother, is a rare privilege indeed.

Following these two tributes, I texted: “Double ditto.”

Then the third sister chimed in:

I can’t add anything – you have expressed it so well, however, I also feel very fortunate that we knew all along how remarkable our parents were – we didn’t have to grow old to discover in “hindsight” how wonderful they were. It was a gift to be able to appreciate them while we had them here. It is a glorious perfect Dad day in NY – lovely blue skies, perfect temperature, and glorious green everywhere.

Absent my oldest sister’s opening text, I don’t know when—or even if, though presumably so—I would’ve remembered today as “Dad’s day.” Surely I would have upon dating this post, but given my writing routine over the past year or more, that wouldn’t have occurred until just before midnight. The fact is, hardly a day passes when I don’t think of Dad.

In many cultures the mourning period following the death of a loved one is exactly one year. This tradition, apparently, was inculcated into my own psyche after Dad died this month 15 years ago. Every single night for exactly a year after his passing, he appeared in vivid form in my dreams. He then moved away from my Land of Nod, though he continues to make regular return visits. (My mother likewise made nightly appearances for a year, then reduced her sojourns to periodic check-ins; grandparents, uncle and a violin teacher appear occasionally too, though all have been deceased for quite some time.) During waking hours, I feel Dad’s presence and influence in powerful ways.

Much of this feeling turns on an extensive overlap of our interests—music, the study of history and geography, admiration of trees, wandering the woods of Björnholm[1], project problem-solving, “design-and-build” projects, and the finer details of the practice of law and the many quandaries that are associated with it[2]. We also shared an obsessive interest in politics, finance and economics, though our opinions were often divergent.

At times our differences were pronounced—to our mutual irritation. Dad was more than disappointed in my hot-headed challenges of his political positions. He was indignant over them. For my part, I found his implacable rigidity frustratingly narrow-minded, closed off from critical considerations. Worse, he’d let his emotions get the better of him and lead him to shout, turn all red in the face, and ultimately, stand up, jam his chair into the table and storm away. I, being of a similar disposition, would all too often match him chair-for-chair. For all his reading and thinking, he seemed psychologically pre-disposed to cutting off his expansive curiosity and high-level reasoning. He was an incorrigible military hawk when it came to deployment of force to advance (perceived) national interests abroad and an equally strident economic hawk when it came to government spending on social services. He uttered the word “program” with as much contempt as he assigned to “Democrats,” “tax and spend,” and “government”—despite the fact that for over three decades, he worked for the “government.”[3]

But with the passage of time the frequency and intensity of our disagreements diminished. Our earlier arguments now seem petty and de minimis. What stand out about Dad are the qualities that my sisters cited in their texts. Yet, what speak to me even beyond those attributes were his deep caring about everyone and everything he thought worthy and his exceptional moral and intellectual integrity.

Everyone in the family knew from the very outset that Dad’s love for us was unlimited and unconditional. Moreover, this love wasn’t parceled out in memorable doses at certain predictable junctures and on special occasions. It was in every word and gesture toward us, and at the same time he had no favorites among the four of us, each of us was made to feel equally important to him. This equally fair treatment came naturally to him, but a degree of intentionality might have driven it too: perhaps he knew that his approach would bind us siblings together better throughout our lives. It wasn’t until after Dad’s death that I discovered the impressive cache of letters in the attic that revealed through thick and thin, just how devoted Dad was to our mother. (See my Inheritance series during the summer of 2023).

Dad’s perfectionism could drive a person crazy. The upside was that everything he touched, intellectually, artistically and practically applied was of the highest quality. None of his attempted accomplishments fell short of his gold standard. The downside of his perfection was that he couldn’t suffer fools—lightly or otherwise. Moreover, as he was quick to point out to us, fools[4] seemed to be running most things in the world. In the main our mother was far more forgiving of people’s weaknesses and deficiencies. If a friend in a dirty car pulled up to the house, Mother could look past the car and say something complimentary about the person. In a disapproving tone, Dad would point out the dirty car and wonder aloud if that’s how the visitor (and spouse) maintained their yard. And while in Mother’s assessment, her Democrat friends had “a different way of seeing things,” in Dad’s mind, they had “a bunch of screwy ideas.”

It took time for me to separate my love and admiration for Dad from the shackles of his perfectionism-in-all-things and various intolerances. The two—perfectionism and intolerances—seemed to go hand-in-hand, and they were such ingrained traits, I couldn’t reasonably expect them to change. When in his last months he once allowed that “I was wrong about some things,” I gave him liberal credit.

Yet, outweighing the downside of Dad’s perfectionism and intolerance of imperfection in others was a single conversation we had many years before he died. The exchange occurred over lunch at the cabin at Björnholm. He was retired by this time and with Mother was stationed at his Shangri-La for the summer. My immediate family was up for the weekend. A few days earlier Dad had taken delivery of some project building materials from the Hayward lumber yard, and over soup and sandwiches Dad was grousing volubly over the damage caused by the “careless” driver of the delivery truck.

“He was driving too darn fast,” said Dad, “and as he passed the garage, a side of the truck ripped into the corner of the soffit. Now I gotta order more lumber and repair it.”

“Geez, Dad,” I said, “the lumberyard should compensate you for it. It was their guy’s fault.”

“No, no, I don’t wanna do that.”

“Why not?” I asked in puzzlement.

“He was a fairly young guy. Probably married with young kids, and I wouldn’t want him to lose his job over it.”

I said nothing, but I would never forget what Dad’s surprising response said about his character, and I vowed to emulate his forgiving spirit in my own dealings with other people—however flawed, weak and deficient I might find them.

If the perfectionist’s perfectionism was his imperfection, Dad’s character was imbued with overriding impeccable qualities; traits that made the world a better place by his quiet but abiding influence on the people around him, who, in turn, influenced many more, wittingly and unwittingly, which is how collectively we can make a profound difference on how the world spins.

God knows I miss him. All who knew and loved him miss him, most especially my three sisters, who, as it turns out hands down, were the best three sisters our parents could’ve given me.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] I remember a time when Dad and I were seated next to each other on the front steps of the cabin, admiring the lacustrine beauty in front of us. It moved him to say, “This place makes gives me great contentment even when I’m not here . . . Just knowing that it exists brings me untold satisfaction.”

[2] Though Dad never obtained a law degree, as the district court administrator for what during his long tenure in office was the fastest growing county in the state, he observed the work of many lawyers. Ever the perfectionist, he found the many flaws in their work. Very active in his professional association, Dad devoted considerable time to lobbying and helping craft legislation applicable to court administration throughout the state. His work was highly regarded by all who knew about it. He took special interest in my work and loved hearing about my various challenges in the practice of law and management of a business line at the bank. Besides my brother-in-law Dean, Dad was the only one in the family who was both genuinely interested in and knowledgeable of the waters in which I sailed and swam.

[3] Since 2015 I’ve wondered periodically, Would Dad have been disgusted enough by Trump not to have voted for him? Each time, I resolve the question in a manner that is aligned more with my hope and reasonable expectation than by the fear that he might’ve pulled the “wrong” lever had he lived into the MAGA era.

[4] Or on occasion, “us fools” (no comma).