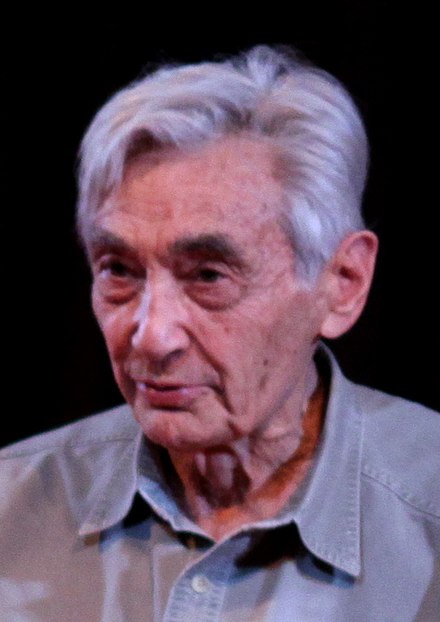

FEBRUARY 9, 2025 – (Cont.) First, let’s take those first 150 pages of the 680-page history tome. The book is A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. I’m positive that several of my readers have read all 680 pages of it; that additional readers know of the book and are generally familiar with its unabashedly leftwing thesis. Not surprisingly, the work has been heavily condemned by people who don’t share Zinn’s bias. Objectively, the book is rightfully criticized for its poorly documented references and heavy dependence on secondary sources. If I’d been Professor Zinn’s editor, I’d have taken him to task for these deficiencies and sent him back to the research drawing board . . . er, his graduate student assistants. Frequently, I find the book’s lack of rigor in supportive citations to be downright exasperating. Nevertheless, I’ve studied enough history, reaching back to my formal education[1] to know that a preponderance of evidence supports Zinn’s basic thesis: ever since the settlement of Jamestown in 1607, monied interests and white men have dominated the social, political and economic landscape, not to mention the physical development of the United States.

A client had presented Zinn’s book to me as a thank-you gift nine years ago. Inside the front cover, he’d penned a long inscription about the work, ending with, “This book changed me profoundly.” Said client is a fellow lawyer with whom I enjoyed many serious discussions about politics back when we were in the same office building—predating Trump 1.0. He was quite brilliant and extraordinarily well informed; a highly analytical thinker, whose intellectual integrity was beyond reproach. He was as biased as anyone with strong opinions, but those opinions were grounded in facts, not fiction, and psychologically he was fully capable of standing in the shoes of other people to understand “where they were coming from.” His ability to do this as an experienced litigator thus came naturally.

Not until recently, however, have I gotten around to embarking on the long, arduous journey into Zinn’s magnum opus. I’d long been familiar with the book, but apart from a couple of reviews I’d read—and forgotten—long ago, I hadn’t even mapped out the book’s protracted route through American history from the founding of Jamestown through the 2000 general election.

From the starting line, it’s important to confront Zinn’s biases[2]—that is, to “know the historian,” as my current professor of Russian history, Theofanis Stavrou, advised in his introductory lecture two weeks ago.

The son of working class Jewish immigrants (pre-WW I; father from Austro-Hungary; mother from Irkutsk Siberia (of all places—I’m sure there’s a story behind that)), Zinn grew up in Brooklyn, living on the economic margin. His father worked as a ditch digger, window cleaner and waiter at bar mitzvahs. The best that his parents could provide to supplement his education was 10 cents and a coupon for each of the 20 volumes works by Charles Dickens published by the New York Post. A central theme of Dickens, of course, was social and economic oppression.

As an impressionable young man Zinn wound up hanging out with Communists (!) in Brooklyn. One day they invited him to tag along for a peaceful rally in Time Square. The mounted cops, however, would have none of the gathering, peaceful or otherwise, and charged the demonstrators to disperse them. Zinn was knocked unconscious, and the rest was history, you might say: when he regained consciousness, he found that the smack-down had made an indelible impact on his worldview.

After graduating from Brooklyn’s Thomas Jefferson High School[3], he became a shipfitter, working under hazardous conditions. As an apprentice, he was barred from joining the union, so with other apprentices, he formed a union-like association that met regularly and read radical political literature. This experience reinforced the earlier smack on the head in Time Square.

With the outbreak of WW II Zinn was initially opposed, but in time he woke up to the threat of fascism (we’re left to think that Zinn was inexplicably oblivious to the Nazi crackdown on its Jewish population, though most of America at the time was ignorant or dismissive of the persecutions in Germany). He joined the Army Air Corps and served as a B-17 bombardier on raids over Berlin, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, and late in the war, a bombing run over Royan, France on which Napalm was dropped.

After the war, Zinn returned to Royan to conduct post-doctoral research. It was through that research that he learned the horrific scale of destruction that his raid had unleashed: a thousand civilian casualties (along with German soldiers hiding outside of town waiting for the war to end). Zinn concluded that the Royan bombing—executed just three weeks before VE-Day—had been based less on legitimate military objectives and more on American military figures seeking advancement.

Similarly in the case of his outfit’s earlier bombing run over Pilsen, Zinn learned after the war that the official history of the Eighth Air Force (his group) claimed that 500 tons of “well-placed” bombs had been dropped on the enormous Škoda Works but that given the Americans’ pre-raid warning, all the workers but five had escaped before the facility was blown to smithereens. But Zinn knew better than what the official story told. As deputy lead bombardier on the raid, Zinn was aware that no such precision bombing had occurred. The bombers had unloaded their payloads over Pilsen indiscriminately, and when he returned to the city after the war, he learned from two Czechs who’d survived the raid that hundreds—not just five—people had perished.

His war experiences informed Zinn’s extensive anti-war activities during the Viet Nam War—and fed the bias of his writing about that dark chapter of American history.

After WW II, Zinn obtained his B.A. from NYU (on the GI Bill) and pursued his masters and PhD at Columbia, where he studied with the very profs whose works showed up on my history course reading lists—Donald, Commager, Hofstadter. In 1956 he began his teaching career at Spelman College—until he was fired in 1964 for having allegedly “radicalized” his students. Ironically, the Black institution didn’t approve of Zinn’s heavy involvement in the Civil Rights Movement (mainly working with SNCC (the “Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and his support of students’ civil disobedience in protest of segregation.

He “transferred” to Boston University, where he taught for the rest of his career. Not surprisingly, Zinn’s non-required course on civil liberties was one of the most popular courses at BU, attracting as many as 400 students every semester.

Right-wingers today would have a collective cow if they found A People’s History of the United States in a public school library, let alone public high school classroom. Removal of “People’s” from the title, however, might save the book from the pyre—initially, at least—when the New Order really fires up against intellectual freedom.

Tomorrow I’ll explain why Zinn’s book figures so prominently in my current “crisis of perception.” (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Beginning in high school I was fortunate enough to have instructors who were serious students of history and who buried their students with reading lists that were obscure when presented but that I later discovered featured works from the pantheon of American history scholars, from Frederick Jackson Turner to Richard Hofstadter to William Steele Commager to Bruce Catton to David Donald to Edmund Morgan to John Lewis Gaddes to Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. In college history courses, I learned the role of primary sources in evaluating “authority” and supporting theses.

[2] Of course Zinn is biased. Every historian is. It’s no more possible for an historian to by non-biased than it is for a painter to create a picture without paint. Likewise, it’s impossible for the student of history not to be biased, just as it’s impossible for the visitor of an art museum not to view art through an unbiased filter. That being said, the more history one reads, just as the more art one studies, the broader becomes one’s perspective and “big picture” understanding of history and art.

[3] The school was known for the arts, literature and creative writing program under the guidance of Elias Lieberman, its principal from 1924 to 1954. Lieberman was a poet and prominent educator, whose family immigrated from Russia in 1903—around the time Zinn’s parents had (his mother, from Russia).